The mainstream media have been vocal in their condemnation of the so-called student riots. An alternative view is offered by Aberdeen student Gordon Maloney, an activist in the protests.

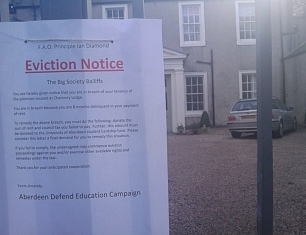

The last couple of months have been incredibly exciting for student activists. Four of the biggest student demonstrations in recent memory have taken place within a month of each other, and between these there has been continuing news of University occupations, demonstrations and stunts across the country.

In the beginning, these actions were more or less focused on the Coalition’s proposed increase of the cap on tuition fees and abolition of the Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA) in England and Wales The focus has since broadened significantly and action is bound to accelerate since the government’s success in raising the cap.

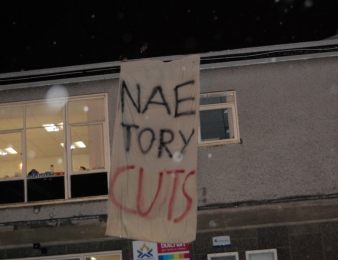

“What are you protecting? Your job’s next”, protesters chanted at lines of masked, baton-wielding police between horse charges and demonstrator scatterings on the day of the vote. These protesters – many of them school children – have come to understand more quickly than some other sectors of UK society, the extent to which the same reckless cuts to further and higher education will decimate jobs, services and communities across the country.

After the damage done at Millbank in the first demonstration, many in the student movement seemed concerned not with the damage done per se, but rather that it provided the government and the right wing media with the opportunity to de-legitimise the protest altogether and to dismiss what happened as the work of “socialists and anarchists” – not students – as if these terms were somehow exclusive. We were repeatedly told that images of masked students smashing windows, graffiti on police vans or students throwing bits of placards at police would be used against us. They were, but it hasn’t worked.

When our marches were kettled and we were denied our right to protest, anger boiled over

This tactic, employed so successfully by the right after G20 in 2009, seems to have failed this time. At the time of writing, a Daily Mail poll asking, “Do you still support the students after these riots?”, showed that 76% of respondents do. Since September, I have spent countless hours campaigning and speaking to people on university and college campuses and around areas without large student populations. The only difference I have noticed in people’s attitudes after the protests is a much greater awareness of the issues. People have heard about the fee increase, the broken pledges and the scrapping of the EMA. They have, of course, also heard of smashed windows and burning placards, but they understand that this just showed the scale of anger of demonstrators.

The people I speak to understand that we have already gone through the democratic process. We have had the debates, and in terms of public opinion we have quite convincingly won. We even won the election. A party which pledged to abolish tuition fees altogether is in government. People demonstrating already felt betrayed not just by the Liberal Democrats, but by democracy. When our marches were kettled and we were denied our right to protest, anger boiled over. Criticism of this has been less widespread than might be imagined.

It seemed that the only outcome of the damage to property – I refuse to call it violence – was to ensure widespread coverage of the events.

It is easy to argue that it is understandable that people broke windows at Millbank. It is also reasonable to argue that, faced with cuts as potentially devastating as we are, it was proportionate. The question then becomes one of necessity. Would the 10 November demonstration have acted as such a catalyst for future demonstrations if it had remained, as NUS President Aaron Porter wished, a peaceful A to B march? Would it have changed anything at all? Realistically, probably not.

Despite the repeated mantra that protestors have gone on demonstrations intent on chaos, nobody at these protests wanted to be violent. This was made crystal clear to me when I saw a lone policeman trip up in the middle of a crowd of protesters who, just a minute before, had been pushing police lines and throwing sticks. Nobody touched him. Not because they were scared of repercussions, but because that wasn’t why they were there. People backed away from him, allowed him to get up and return to the line of police.

Damage to property shouldn’t be necessary for people to be heard, but in a society that seems to care more about paint being thrown on a car than the well-being of an innocent man who suffered a brain haemorrhage as a result of a police attack, it seemed to many demonstrators that there were few alternatives. Michael Gove told reporters, on 24 November, that the Government would, “respond to arguments….not to violence”. We have had, and won, the arguments. They didn’t listen, and they can expect more of the same if they continue not to listen.