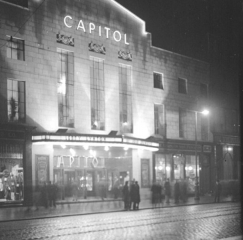

As another demolition threat looms over Union Street’s once great Capitol, new Aberdeen Voice writer Murray Henderson looks at the fortunes of Aberdeen’s slumbering star of the silver screen.

“Aberdeen’s most prestigious cinema. Its facade is of classical proportion. In the centre, soaring above the entrance is a simple pediment, which originally carried the name “Capitol” in neon letters. Inside, grand staircases swept up to the lofty circle and stalls foyers. In the auditorium was the great Compton Organ, whilst Holophane lighting glowed seductively. The Capitol is unique, an outstanding building which deserves a full restoration.”1

– The Theatres Trust.

The Capitol Cinema once captivated Aberdonians with the latest movies and an Art-Deco interior direct from a Hollywood set.

It is one of the few remaining ‘super cinemas’ from the pre-war boom, akin to the Brixton Academy or the Edinburgh Playhouse.

Though the last film was shown in the 1960s, the Capitol continued to host rock concerts2 as late as 1998.

A hammer blow to the Capitol came in 2002 with the arrival of Chicago Rock/Jumping Jacks and their proposal for two separate nightclubs.

Despite public objection, Historic Scotland backed the plans and the council voted in their favour,3,4 enabling sweeping modifications to be made to the building.

The auditorium was split horizontally in two and an all new identity, which destroyed much of the original character, was imposed. The Theatres Trust condemned the alterations as “brutal” and “a disgraceful failure of the historic building control system,” comparable only to one other in the UK, the Philharmonic Hall in Cardiff.5

In 2009, the Chicago Rock/Jumping Jacks owners entered receivership and the clubs were closed. The credit crunch, the smoking ban and cheap supermarket alcohol were cited as reasons for their demise.2 In 2010 another planning application was submitted for full demolition of the Capitol’s auditorium and an eight storey hotel and office development being built in its place. The plan was granted approval though never implemented.

As details emerge about the new proposals, the future of the Capitol is once again in the hands of developers and a city council which believes there is neither the money nor the public demand for its restoration.2

According to the British Film Institute (BFI), this story is common across the UK. Traditional cinemas have been unable to compete with the multiplexes and their closures have contributed to the decline of many city centres. The BFI attributes this to the multiplex’s larger screen size, improved sound quality, better choice of films and greater all-round convenience.

But typically, their design is uniform and unadventurous, with many resembling industrial warehouses. Inside, multiplex auditoria are bland, blank voids, utilising the ‘black box’ concept in which the viewer has the least possible distraction from the screen.6

Despite the dominance of multiplexes, there are pockets of resistance. The old mining town of Bo’ness had, in the dilapidated ‘Hippodrome’, Scotland’s first purpose-built cinema. After languishing in a state of neglect for 30 years, the cinema was recently restored in spectacular style and this year proudly celebrated its centenary.

According to the Theatres Trust, community stewardship is often a theatre’s best chance of salvation. However, this takes hard work, dedication, and significant funding, which can come from grants or philanthropic sources. If the theatre is saved, the hard work continues in maintaining a programme of events and ensuring it is financially viable.7

This model is driving another success story in Glasgow in the Britannia Panopticon, the oldest surviving Music Hall in Britain, which at one time also functioned as a cinema. With members of the public as curators, a charitable trust has been set up with the goal of full restoration. Regular shows have resumed and the importance of the building is now being realised by the wider public.8

These examples show that a niche does exist for cinemas like the Capitol. Their distinctive architecture gives a true sense of theatre befitting the drama on screen which the drab, corporate, multiplex cannot rival. Their survival depends not only on the extent of historical alterations made to them but, perhaps more importantly, on how much they are valued by the public and city councils, as part of our heritage.

It is clear that in its current situation, the Capitol Cinema has a considerable mountain to climb if it is to join the Hippodrome, or the Britannia. But cinema’s greatest stars do have the habit of making the most unlikely comebacks. In the Capitol’s case, the show is not over until the curtain comes down.

References

- Theatres Trust “Guide to British Theatres 1750-1950”

- Aberdeen Council Planning Decision Notice for Application, Ref: P101757

- Aberdeen City Planning Committee Minutes 18th April, 2002.

- Aberdeen City Council Meeting Minutes Town House, 1st May, 2002.

- www.theatrestrust.org.uk

- British Film Institute Website

- email correspondence with The Theatres Trust.

- email correspondence with the Britannia Panoptican Music Hall.

- Comments enabled – see comments box below. Note, all comments will be moderated.