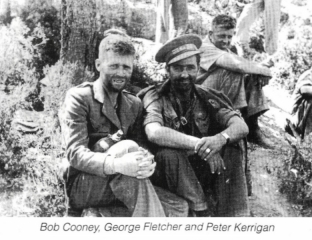

In a time before widespread international travel, Bob Cooney would journey across continents to realise the depths of his beliefs. He would find himself at the sharp end of unfolding events that would prove to be of considerable historical significance. In the second part of the trilogy written by Bob’s nephew – Aberdeen City Councillor Neil Cooney – we learn how Bob would selflessly bring his talents and convictions to bear to oppose fascism, both at home and in Spain, and with increasing vigour, passion and heroism – to say nothing of intense mortal danger.

Bob missed most of the 1931 crisis because his life had entered a new phase. In 1930, he packed in his job as a pawnbroker’s clerk in order to devote himself full time to politics.

It was a brave decision, his new job carried no wages but it did give him an opportunity for further education.

He spent thirteen months during 1931-32 in Russia, studying by day in the Lenin Institute, working by night in a rubber factory.

There he picked up an industrial throat infection and spent some time in a sanatorium. It left him with huskiness in his voice that became part of his oratory. Times were tough in Russia but good in comparative terms with the destitution of the Tsarist era.

Bob found a thirst for knowledge that was infectious throughout Russian society. Even grannies were going back to classes to learn the skills to make their country prosperous. There was even time for a glorious holiday down the Volga. It charged up his batteries for the tasks ahead. He was not short of work when he returned in 1932.

There was a lot of heavy campaigning to do, to mobilise the unemployed and to organise the hunger marches. He travelled from Aberdeen to Glasgow and Edinburgh speaking at open-air meetings to campaign against unemployment, to rally public opinion against the iniquitous Means Test, which robbed the poorest of their Dole as well as their dignity.

Fascists in Aberdeen

Out of the turmoil of the Depression came the strange phenomenon of the British Union of Fascists. Oswald Mosely, its creator, had served in both the Tory and Labour camps before forming his Blackshirts. He was copying the style of Mussolini and was both influenced and funded by Hitler. His area Gauleiter for the North was William Chambers Hunter, a minor laird by inheritance.

He had started off life as plain Willie Jopp but now he had pretensions of power. Aberdeen was targeted as his power base and he recruited and hired thugs from afar afield as London to help him take over the city.

Bob and the others decided to stop him.

There were pitched battles, arrests, fines and imprisonment, but they succeeded. Fascism was not allowed to take root in Aberdeen. Those who deny the free speech of others did not deserve free speech themselves.

Aberdeen has a tradition of fairness. No trumped up laird was going to destroy it. Bob emerged out of these pitched battles as a working class hero. He displayed his undoubted courage as well as his often under-rated organisational skills. It wasn’t enough to stand up to the Fascists, you had to out-think them and outnumber them and run them out of town.

The first Fascist rally organised for the Music Hall, to be addressed by Raven Thomson, Mosely’s Deputy, had to be cancelled half an hour before it was due to start.

The Fascists eyed the Market stance as a key venue. It had become a working class stronghold. The key battle was to take place there.

Chambers Hunter pencilled in the evening of Sunday 16 July 1937 for his big rally. The workers would be caught out on a Sunday in the height of the holiday season. He miscalculated. The grapevine was finely tuned; and Bob addressed a crowd of 2,000 at the Links at 11a.m. They vowed to gather at the Castlegate in the evening. The Fascists duly arrived with their armour-plated van and their police escort, their amplifiers and their heavies.

Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy gave immense aid to the Spanish Fascists

As Chambers Hunter clambered to the roof of the van, the workers surged forward, cut the cables and chased the Fascists for their lives. The Castlegate was cleared by 8 p.m. Bob was one of many arrested, and served four days for his efforts.

A young Ian Campbell, later of folk music fame, remembers sitting on his father’s shoulders watching Bob being carried shoulder high on his release from prison. He also remembers how the crowd went silent as Bob addressed them. It was Bob’s last speech in Aberdeen for a long time because within hours he was on his way to Spain.

In Spain in 1936, the army revolt triggered the Nationalist Right-wing attack on the democratically elected Republican government. Despite the terms of its Covenant, the League of Nations opted for a policy of “Non-Intervention”. Eden and Chamberlain were quick to agree, even though such a policy guaranteed a Franco victory.

It provided a precedent for our later inaction in Austria in the spring of 1938 and Czechoslovakia both in the autumn of 1938 and in the spring of 1939. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy gave immense aid to the Spanish Fascists. Stalin’s Russia gave much more limited aid to the Republicans. International Brigades of volunteers were also formed to aid the Republic.

The Go-Ahead for Spain

‘And if we live to be a hundred

We’ll have this to be glad about

We went to Spain!

Became the great yesterday

We are part of the great tomorrow

HASTA LA VISTA – MADRID!’

– Bob Cooney

Bob had pleaded for months to go to Spain but the Communist Party kept stalling him, saying he was too valuable at home in the struggle against the Blackshirts.

In the spring of 1937, he set off from Aberdeen but was again stopped by party HQ. It wasn’t until the Castlegate victory that he eventually got the go-ahead from Harry Pollitt, the party’s General Secretary. Bob had argued that he felt hypocritical rallying support for the Spanish people and urging young men and women to go off to Spain to help the cause, and yet do nothing himself. Thoughts of Spain filled every moment of every day – the desire to fight for Spain burned within him. He later reflected that participation in Spain justified his existence on this earth. Spain was the front line again Fascism. It was his duty as a fighter to be there.

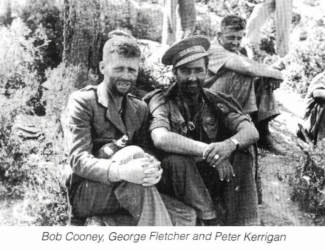

Bob was 28 when he left for Spain, getting there via a tortuous route; a tourist ticket to Paris, followed by a bus to Perpignan and then a long trek across the Pyrenees to Barcelona and beyond. He got five weeks basic training at Tarragona, a small town close to the modern resort of Salou.

There he was given his ill-fitting khaki uniform, strong boots, a Soviet rifle and a food bowl. He was appointed Commissar (motivator) of the training group. He was offered officer’s training but refused. He had promised Harry Pollitt that he was there to fight, not to pick up stripes.

Bob eventually was promoted to the position of Commissar of the XV (British) Brigade. The Brigades were integrated with local Spaniards. Bob, to lead them, had to learn their language. They soon caught on to his wry sense of humour.

His first action was at Belchite, south of the Ebro. He always said he was afraid to be afraid. He told his men never to show fear, they weren’t conscripts, they were comrades and they would look after each other. He had to prevent their bravery descending into bravado. There were some who vowed never to hide from the Fascists and to fight in open country. This would have been suicidal and such romantic notions had to be curbed.

Bob served in two major campaigns. The first was at Teruel, between Valencia and Madrid. The Brigade was drafted in to hold the line there in January 1938. Paul Robeson, the great singer, dropped in to greet them there: Robeson was heavily involved in fund-raising for the Spanish cause. The XV Brigade held their line for seven weeks before Franco’s forces complete with massive aerial power and a huge artillery bombardment forced them back.

Conditions were hard, supply lines were tenuous and the food supply was awful. Half a slice of bread a day was a common ration. His next great battle was along the Ebro from July to October 1938.

On a return sortie to Belchite, organising a controlled retreat through enemy lines, he was captured along with Jim Harkins of Clydebank. Another group on the retreat distracted their captors and Bob and Jim fled for cover. Sadly, Jim later died at the Ebro.

Just over 2,400 joined the Brigades from Britain, 526 were killed, and almost 1,000 were wounded. Of the 476 Scots who took part, 19 came from Aberdeen. The Spanish Civil War claimed the lives of five Aberdonians, Tom Davidson died at Gandesa in April 1937 and the other four at the Ebro. Archie Dewar died in March 1938, Ken Morrice in July 1938, Charles MacLeod in August 1938 and finally Ernie Sim in the last great battle in September 1938.

The final parade of the Brigade was through Barcelona on October 29th. They were addressed by the charismatic Dolores Ibarruri who had been elected Communist MP for the northern mining region of the Asturias: she was affectionately known as La Pasionara. She told them:

“you can go proudly. You are legend. We shall not forget you”.

It had taken the combined cream of the professional forces of Germany, Italy and Spain almost three years to beat them. They had every right to be proud. Barcelona fell to Franco late in January 1939, Madrid falling two months later.

Dont miss the third and final part of Neil Cooney’s account of his Uncle Bob Cooney’s amazing story – when we learn that Bob Cooney has barely time to reflect on the events relating to the Spanish Civil War before joining the fight against Hitler and the Nazis.

By Duncan Harley.

By Duncan Harley.