To coincide with the unveiling of the Robert The Bruce statue at Marischal College, Voice’s Alex Mitchell presents the second of a three part account of King Robert’s life, his impact on historical events, and the role of powerful rival family the Comyns.

Given that England was a larger, richer, more technologically-advanced and much more populous nation than Scotland, it was inevitable that continued warfare between England and Scotland would, in the long term, result in victory for England, if only by a process of attrition – loss of fighting men.

The Scots might win the occasional battle, as at Stirling Bridge, but the English – even under a king less ruthless and determined than Edward I – would eventually win the war. Scotland could survive as an independent nation-state only by arriving at a modus vivendi with England.

Wallace’s famous victory at Stirling Bridge was followed, less than a year later, by utter defeat at the Battle of Falkirk on 22 July 1298. After a further period of unsuccessful guerrilla warfare, Wallace resigned the Guardianship. He was never again in command of a large body of troops.

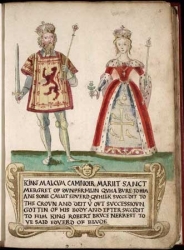

John (the Red) Comyn of Badenoch and Robert Bruce were made joint Guardians. They were also the leading Competitors for the Scottish throne. John Comyn’s mother was Marjory, sister of King John Balliol; the Comyn had an immediate claim to the Scottish throne should anything happen to Balliol’s sons, Edward and Henry, who were both minors and captives of the English. John Comyn’s claim to the throne was, in fact, slightly stronger than that of Bruce. There was a violent altercation between Comyn and Bruce in Selkirk Forest in 1299, during which Comyn came close to killing Bruce.

King Edward invaded Scotland again in 1300, 1301 and 1303; he entered Aberdeen in late August 1303. He captured Stirling Castle, the last fortress to hold out against him, in the summer of 1304. But Edward was by political and economic necessity a compromiser, preoccupied by his campaigns in France. He could not afford the huge expense in terms of manpower, money and materials required to subjugate Scotland as he had crushed Wales. So Edward had little choice but to enter into bonds and alliances with his former enemies in Scotland, the Bruces and the Comyns.

Robert Bruce had resigned the post of joint Guardian, and made his peace with King Edward. In 1302, he married Elizabeth de Burgh, daughter of the Earl of Ulster, one of Edward’s closest allies. Other Scottish nobles, including allies of the Comyns, and eventually, by 1304, the Comyns themselves, decided to accept the reality of the situation and similarly elected to make their peace with King Edward.

William Wallace was captured by the English, and was hung, drawn and quartered at Smithfield in London in 1305. The same traitor’s death had been inflicted a few years earlier on the Welsh leader, Dafydd ap Gruffudd. Neither he nor Wallace were traitors in any meaningful sense, never having sworn allegiance to King Edward.

Bruce was now an outlaw. He and his supporters seized as many English-held castles as they could.

The issue as to who should be King of Scotland remained unresolved. Robert Bruce offered the Comyns all the Bruce estates if they would support his claim to the throne. Bruce and the Red Comyn met at the Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries on 10 February 1306.

In the course of an argument – Comyn seems to have neither approved nor supported Bruce’s plan – Bruce drew his dagger and stabbed Comyn in the throat. Bruce’s two brothers attacked Comyn with their swords and then killed his elderly uncle, Sir Robert Comyn. Bruce had not merely murdered the head of the Comyn family, but had done so in a consecrated place – an act of sacrilege, which might, at least, suggest that the crime was not pre-meditated.

Bruce was now an outlaw. He and his supporters seized as many English-held castles as they could. John Balliol’s kinsmen and supporters fled south. King Edward persuaded the Pope to excommunicate Bruce from the Church.

Bruce was enthroned at Scone the following month, on 25 March 1306 – the tenth anniversary of the outbreak of war between King Edward I and the Scots. The new King Robert I was crowned by Isabel, the young Countess of Buchan, who stood in for her 16-year old nephew Duncan, Earl of Fife, who held the hereditary right to crown the Kings of Scotland, but who was completely in the power of King Edward of England.

Isabel’s participation in this makeshift ceremony contradicted the interests of her husband, John Comyn, Earl of Buchan. She was captured by the English not long afterwards, and was imprisoned in a wooden cage fixed high up on Berwick Castle. She was moved to a less harsh confinement after four years, but there is no evidence that she was ever set free.

With their enemy Robert Bruce now crowned King, the Comyns and their allies – men whose patriotic credentials and record of public service were far more impressive than those of Bruce himself – took the view that they had little choice but to side with King Edward of England. This was to be the downfall of the Comyns.

Atrocities were committed, not by the English, but by Scots against their fellow Scots

Even leaving aside Bruce’s obvious skills as a soldier and political strategist, most ordinary folk were bound to identify themselves with a new and successful King of Scots rather than a discredited Balliol/Comyn faction, inevitably tainted by the perceived failures of the exiled King John and, moreover, aligned with the hated Edward of England.

Scotland was plunged into a civil war between the Balliol/Comyn faction and the Bruces and their supporters. Robert Bruce himself was a hunted man, on the run for over a year, during which two of his brothers were killed. But the once-terrifying Edward I was now 68 years old and mortally ill; he died on his way to Scotland on 7 July 1307. His son and heir, Edward II, was not, to put it mildly, the man his father had been.

Bruce came out of hiding. Aided by his chief lieutenant, Sir James (the Black) Douglas, Bruce won a series of victories against the Balliol/Comyn elements of the Scottish nobility. The clans rallied to his side. He defeated the Comyns, under the leadership of John Comyn, the Earl of Buchan, at Old Meldrum (Inverurie) in May 1308. John Comyn fled to England, whilst Bruce, who was seriously ill, holed up in Aberdeen.

His brother, Sir Edward Bruce, chased the remnant of Comyn’s men into deepest Buchan, where they were again defeated at Aikey Brae, near Old Deer. There followed the Herschip (Harrying) of Buchan, undertaken with the sole objective of the destruction of the Comyn power base in the north-east of Scotland. Atrocities were committed, not by the English, but by Scots against their fellow Scots. Bruce had his men burn the Comyn earldom of Buchan from end to end, until the whole of the north-east swore allegiance to him.

In 1310, Bruce commenced a series of devastating raids into northern England. In 1311, his troops drove the English garrisons out of all their remaining Scottish strongholds and castles, except Stirling, and he invaded northern England.

King Robert certainly showed considerable gratitude and affection towards Aberdeen and its people

King Edward II finally led a huge army into Scotland in 1314.

Bruce achieved a decisive defeat of the English at the Battle of Bannockburn, near Stirling, on 23-24 June 1314, during which the murdered Red Comyn’s only son and heir was himself killed whilst fighting on the English side.

In 1315, Bruce’s brother Edward invaded the English colony in Ireland and threatened Wales. But it was not until 1328, after the horrific murder of Edward II, that the regents of the young King Edward III finally offered the terms of peace resulting in the Treaty of Northampton-Edinburgh, which recognised Scotland as an independent kingdom and Robert Bruce as its king. By this time, Bruce himself was worn-out and ill. He died in 1329, aged 55 years.

History tends to be written by the victors. John Balliol’s “weakness” was exaggerated by the Bruces and their supporters, so as to justify their own actions. The Comyns were reviled as traitors, for having fought with the English at Bannockburn, but both the Comyns and the Bruces fought on different sides at different times. Both families put their own interests first, and acted accordingly.

Legend has it that the citizens of Aberdeen, who seem to have supported Bruce from the start, attacked the English garrison in the Castle in 1309, and put them to the sword. There is no particular evidence of this – in particular, the historian John Barbour (1320-95) makes no mention of it in his epic poem de Brus of 1375 – but King Robert certainly showed considerable gratitude and affection towards Aberdeen and its people, and spent a disproportionate amount of his time in Aberdeen.

In this he was following the example of previous Kings of Scotland, pre-occupied by the threat from the Vikings in the north. Their power was broken by King Alexander III at the Battle of Largs in 1263 but, even after that, the lowland towns remained under constant threat of incursion and pillage by the Celtic Highlanders. In response, the Scottish kings had built up a defensive framework of castles centred on the great fortress of Kildrummy Castle.

For the first time since the 11th century, the nobility had to decide whether they were to be Scottish or English – they could no longer be both

King Robert lavished gifts and privileges on Aberdeen. The Aberdonians had been amongst the first to rise in defence of the freedom of Scotland; they had been almost his only friends in time of dire trouble.

The Burgh had offered him a refuge when he was ill. He and his son David and their whole family regarded Aberdeen as their own town.

King Robert’s grants and favours to Aberdeen far exceeded in both number and value those he made to other, notionally more important towns, like Edinburgh and Perth. He granted Aberdeen the first of six Royal Charters in 1314, which established the city as a Royal Burgh.

The Burgh was granted the office of Keeper of the Royal Forest of Stocket, which became the basis of the Common Good Fund. In 1319, King Robert amplified his grant into a Great Charter. He bestowed on the burgesses and community of Aberdeen the ownership of the Burgh itself and of the Stocket Forest, in return for an annual payment of £213 6s 8d (Scots).

The lands, mills, river fishings, small customs, tolls, courts and weights and measures were theirs. They could build and develop within the boundaries of the forest – the Freedom Lands, as they came to be known; only the game, the growing of timber and the right of hunting were reserved for the King.

The revenues arising from this bequest gave the Burgh an assured annual income, the basis for real progress and improvement. In 1320, the Brig o’ Balgownie was built across the River Don, funded either at the King’s instigation, or by the King himself. The Brig may have been built to ease the movement of armies northwards, but it greatly facilitated trade with the country north of the River Don, with Buchan, Formartine and the Garioch.

Throughout his reign, King Robert I adhered to the principle that there should be no disinheritance of men (and women) claiming property by hereditary right, provided they were prepared to swear allegiance to him. They could no longer own land in England as well as in Scotland. For the first time since the 11th century, the nobility had to decide whether they were to be Scottish or English – they could no longer be both.

The “disinherited” whom King Robert chose to exclude from the peace terms in 1328 were those who wanted to have it both ways – to enjoy their Scottish lands and yet be subjects of the English king, or vice-versa. To generalise, King Robert imposed forfeiture of Scottish land and estates only on non-Scots who declined to become his subjects, and on those Scotsmen, like the Comyns, who remained to be his irreconcilable enemies.

Alex’s account will conclude in next week’s Voice