Continuing on from Part One of Blood Feud, Voice’s Alex Mitchell offers up yet another slice of Scotland’s troubled and violent history. Last week Alex looked at The Gordon, Forbes and Stewart Families in the Time of Mary Queen of Scots and King James VI This week we see how the fortunes of Clan Gordon changes in the turbulent times of Mary, Queen of Scots.

The Gordons, for their part, held back until the Earl of Huntly was ‘put to the horn’ or outlawed and rendered fugitive on a trumped-up charge of refusing to answer a summons from the Protestant-dominated Privy Council, of which he was still a member.

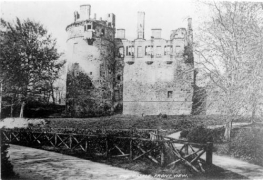

Huntly marched towards Aberdeenwith a force of about 1,000 men, almost all of them Gordon kinsfolk and dependents; no other gentry families joined his campaign to ‘rescue’ the Queen.

He mistakenly believed that many of the Queen’s troops would join his side.

He took up a commanding position on the Hill of Fare, near Banchory, but his men melted away. His troops, now reduced to about 500, were assailed by some 2,000 men under the command of the Earls of Moray, Morton and Athole, and were forced down on to the swampy field next to the Corrichie Burn.

The Earl of Huntly, aged 50, corpulent and in poor health, and suffocated by his heavy armour, suffered a heart attack or stroke, and dropped down off his horse, dead.

Huntly’s body was thrown over a pony and taken to Aberdeen, where it was put in the Tolbooth and gutted, salted and pickled. The body was then taken by sea to Edinburgh, where it was given a more comprehensive embalming. After lying unburied in the Abbey of Holyrood for some six months, the mummified corpse of the one-time Cock o’ the North was brought in its coffin before the Scottish Parliament on29 May 1563 on a charge of High Treason.

The coffin was opened and propped up on end so that the deceased Earl could stand trial and ‘hear’ the charges against him.

Those present included the Queen and Huntly’s eldest son George, himself under sentence of death, later repealed. A sentence of forfeiture was passed, stripping the Gordons of all their lands and possessions, which reverted to the Crown and were redistributed amongst favourites, not least the Earl of Moray.

The Gordon armorial bearings were struck from the Herald’s Roll and the once-great dynasty was reduced to “insignificance and beggary”. Huntly’s body lay unburied in Holyrood for another three years until21 April 1566, when it was finally returned to Strathbogie and interred at Elgin Cathedral.

It has to be said that Mary’s behaviour at this time makes little sense.

Two days after the Battle of Corrichie, Huntly’s son, young Sir John Gordon, aged 24, was ineptly beheaded in front of the Tolbooth inAberdeen, to the visible distress of Queen Mary, who was in residence just across the Castlegate and was seen to observe the proceedings from an upstairs window.

It had been rumoured that the Queen and Sir John Gordon were lovers, although this is unlikely given that Mary was constantly under the guard of the Protestant Lords. They had achieved their twin purposes of destroying the Gordons of Huntly, the leading Catholic family inScotland, and of reassuring those Protestant Reformers suspicious of the Queen’s own Catholic leanings.

It has to be said that Mary’s behaviour at this time makes little sense. She was a devout and observing Catholic herself, yet she acquiesced in the legalised persecution of fellow-Catholics and the forfeiture and redistribution of their land and property.

The assumption has to be that she was not in control of events, partly because she was young and inexperienced and was disorientated by her return to Scotland, a country she had departed for France at the age of five; but also because she was fatally uninterested in the processes and responsibilities of government, seldom attending meetings of her own Privy Council at Holyrood. The judicial destruction of the Gordons of Huntly meant that Mary Stuart had lost her most substantial and dependable base of support, and put her thereafter in the grip of her political and religious enemies.

Mary Queen of Scots was made, probably unlawfully, to abdicate her throne on 24 July 1567, in favour of her infant son James, born 19 June 1566, by her second husband (and cousin) Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley, from whom she was already irretrievably estranged. Mary’s effective reign had lasted just six years, and was over before she reached the age of 25.

The birth of a male heir to the throne meant that she had served her purpose, was now surplus to requirements and was in any case by this time dangerously out of control, having fallen under the destructive influence of James Hepburn (1535-78), the widely-detested 4th Earl of Bothwell, a Protestant, but intensely hostile to England.

The Queen’s remaining authority was destroyed by the sensational murder of her husband Darnley, not yet 22 years of age, at Kirk o’ Field on10 February 1567. Bothwell was instantly identified as prime suspect and the Queen as obviously complicit, an accessory, having gone to great lengths to seduce Darnley away from the protection of his Lennox Stewart relations in Glasgow and back to Edinburgh.

But how much did Mary really know? She would not have stayed overnight in the house at Kirk o’ Field, just inside the Edinburgh city walls, only two miles from Holyrood, if she had known that its foundations were being stuffed with gunpowder. To the end of her life, Mary Stuart was convinced that the plot had been to blow up her and Darnley together. This is unlikely, given that the explosion, which literally blew the house sky-high, took place after Mary had left Kirk o’ Field for Holyrood, which most people took to mean that Mary must have been party to the plot to murder Darnley.

But was she? And which plot? Or whose plot?

No-one as unpopular as Darnley was going to survive very long in 16th centuryScotland; but why murder him in such a sensational, attention-grabbing manner, when he could have been quietly dispatched back at Holyrood? Whatever the case, the ensuing scandal was hugely compounded by Mary’s subsequent marriage to Bothwell (in a Protestant church) on 15 May 1567.

Prior to all this, on 8 October 1565, Mary had restored George Gordon, the eldest surviving son of the 4th Earl of Huntly, to most of his father’s titles, including that of Lord High Chancellor, and some part of his former lands and property. This was little more than two years after the deceased 4th Earl had been found guilty of High Treason, his son George imprisoned and put under sentence of death, and his entire family reduced to “insignificance and beggary”.

Mary was presumably trying to rebuild her support in the North-East, but it was too little, too late. On top of everything else, the 5th Earl’s sister, Lady Jean Gordon, had made the mistake of marrying the Earl of Bothwell at Holyrood on24 February 1566. She was cruelly thrown aside and divorced within the year in order that Bothwell could marry his Queen.

Coming in Part 3: Alex Mitchell analyzes the changes sweeping through all aspects of Scottish life – dynasties rise and fall, clans battle for power and dominance, and religious conflicts dominate.