Voice’s Alex Mitchell tells of the scandalous dissipation of the bequest by Dr Patrick Dun in 1631. Dr Dun bequeathed the Lands of Ferryhill in favour of The Aberdeen Grammar School, the tenants of Ferryhill, and the pupils of poor homes which, if handled appropriately, would today be of immense value.

This is an account of how a bequest of great value was first diverted to wrongful uses, and then almost wholly dissipated, not by an outside body of meddlers, but by the very trustees themselves, in whose hands it ought to have been sacred.

Dr Patrick Dun was the son of Andrew Dun, a burgess of Aberdeen. He was probably educated at the Grammar School, and thereafter proceeded to Marischal College.

In 1607, he took his Doctorate in Medicine in Basle, Switzerland. In 1610, shortly after his return to Aberdeen, Dr Dun was appointed Professor of Logic and a Regent at Marischal College. He was appointed Rector of the College in 1619, then Principal in 1621. He held this office, through very troublesome times, until his resignation in 1649, and died two or three years later.

Dr Dun had an outstanding reputation as a practising doctor. He was a man of substance, and when Marischal College was burnt down in 1639 he contributed handsomely towards the cost of the new buildings. His portrait, by George Jameson, dated 1631, is still to be seen in the Hall of Aberdeen Grammar School.

The Lands of Ferryhill consisted in those days of bogs and whins, fit only for rough grazing, and were described by Francis Douglas even as late as 1728 as amounting to ‘little conical hills over-run with heath and furze … the flat bottoms between them drenched with stagnant water’. The Lands of Ferryhill had belonged to the Trinity Friars, who feued them out to the powerful Menzies dynasty. After the Reformation of 1560, the Lands of Ferryhill became the property of the Crown.

Dr Dun purchased the Lands of Ferryhill in 1629 for, it would seem, no other purpose than to bequest them, and all property thereon, by his Will, dated 3rd August 1631, to the ‘Toune of Aberdeine’ for the maintenance of four masters at the Grammar School. Dr Dun bequeathed the whole of this extensive property to the Provost, Baillies and Council of Aberdeen for this specific purpose. He directed that the rents obtained from these lands should be invested until enough money accumulated to buy another piece of land sufficient to yield, along with the original gift, a yearly revenue of 1,200 merks, this sum being sufficient to pay the basic salaries of the stipulated staff of four masters, including the Rector.

Pupils from poor homes, all those who borne the name of Dun and all children of tenants on the Ferryhill estate were to be taught free of charge. Dr Dun’s Will concludes with a solemn injunction that the mortification, or charitable bequest, shall “stand unalterable, inviolable and unchangeable in all tyme hereafter for ever”.

instead of letting the lands out to rent, the Council proceeded to feu them off by public roup or auction

Dr Dun’s Bequest put the Grammar School on a sound and permanent economic footing, and provided the blessing of free education for boys whose parents could not afford to pay fees. So what happened?

In 1653, when the Town Council assumed control of Dr Dun’s Bequest, the stock or capital in the Trust amounted to just over £74. Rents were added until 1666, by which time the capital amounted to just over £583. The Council considered that this was sufficient to allow them to invest in land, as per the terms of the Will.

However: instead of buying land, as the Will stipulated, the Council lent the money out, without adequate security, to various people, including some of their own number; two Provosts, one Baillie and at least two Councillors, all of whom became insolvent, so that the Trust sustained a heavy loss. Others abstracted interest-free loans.

In 1677 the Council purchased the lands of Gilcolmston, on behalf of the town, for just over £1,444; and charged one-third of this sum to the Dun Trust. This was wholly illegal, given that the capital of the Trust belonged to the masters at the Grammar School. By 1681 the capital had declined to just over £469, of which £287 was earning no interest; of this latter sum, £131 was wholly lost. The Town itself was borrowing freely from the Trust.

schoolmasters were deprived of salaries, and the benefit of free education was denied to those actual or potential pupils specified by Dr Dun

In 1752, William Moir, the tacksman of the Lands of Ferryhill, was bought out by the Council, which now entered into full possession of the property. The income from rents had risen to £102 yearly. However, instead of letting the lands out to rent, the Council proceeded to feu them off by public roup or auction, to the great loss of the Trust.

In 1753, the masters at the Grammar School petitioned the Council for an increase in salaries. A settlement was arrived at, or enforced, which cancelled the Town’s debt to the Trust of £427 and ordained that the balance should be applied to building a new school – the predecessor, on Schoolhill, of the present Aberdeen Grammar School, which dates from 1867 – and establishing an endowment fund for its maintenance. All this was utterly illegal, and contributed to the further dissipation of the Trust, the capital of which had fallen to just £100 by 1770.

The effect of this was that the schoolmasters were deprived of salaries, and the benefit of free education was denied to those actual or potential pupils specified by Dr Dun in his bequest of 1631. Walter Thom, in his History of Aberdeen, published in1811, drew attention to the Town Council’s misappropriation of the Dun Bequest. He wrote: “The injury sustained by the citizens of Aberdeen by the mismanagement of Dr Dun’s bequest is sufficiently apparent, and the turpitude of the crime cannot be palliated by any plea of ignorance … the disgrace attachable to those who abused this valuable institution … (etc)”.

The Education (Scotland) Act of 1872 transferred the control of the Grammar School and the other schools in Aberdeen from the Town Council to a new body, the School Board, which had to look into the whole tangled question of Dr Dun’s Bequest. The capital at this time amounted to just over £3,623. There followed difficult negotiations between the School Board and the Town Council, the upshot of which was that the Council agreed to pay the School Board the sum of £164 annually, being the amount agreed on as the income from Dr Dun’s Bequest, i.e., the feu duties of Ferryhill.

In 1929, the Grammar School, as with the other schools in Aberdeen, was brought once again under the control of the Town Council as a result of the Local Government (Scotland) Act of that year. In 1934, provision was made for a payment of not less than £150 per year to be applied so as to benefit boys attending Aberdeen Grammar School. This was all that remained of Dr Dun’s Bequest.

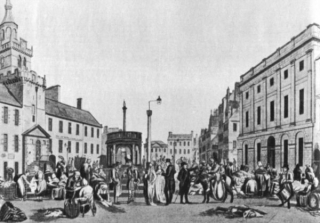

In 1634, when Dr Dun reported to the Town Council his intention to hand over the lands of Ferryhill on behalf of the Grammar School, the total population of the Royal Burgh of Aberdeen was only about 5,000. The town consisted of sixteen streets, centred on the Broadgate and the Castlegate. The lands of Ferryhill – so-named after the ferry across the Dee at Craiglug – were hillocky and marshy, of use for little else but rough grazing by animals. Land of this kind was abundant and of little value.

By the first census in 1801, the population of Aberdeen was about 27,000; it increased almost six-fold over the 19th century to about 150,000 by 1901, and to about 213,000 by 2001. The Lands of Ferryhill, which were wholly built over by 1901, would even then – never mind today – have been an immensely valuable property.

The Trust would have required adjustment following the advent of State-provided and State-financed education but, had it been retained intact and honestly administered by the Town Council, it is easy to imagine what a favourable position the Grammar School – or indeed the whole Burgh – could have enjoyed through the 20th century and today. That this fair prospect has receded into the limbo of frustrated things, of “what might have been”, is due solely to the dishonesty and carelessness of successive Aberdeen Town Councils through the 17th and 18th centuries.

N.B. This article is adapted from an original titled The Tercentenary of Dr Patrick Dun’s Bequest to the School, by W. Douglas Simpson, published in the Aberdeen Grammar School Magazine of 1934.