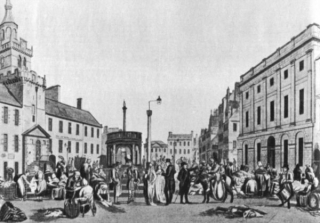

Alex Mitchell continues his historical account of the development of Aberdeen, this week focussing on the old Castlegate.

no images were found

The old Castlegate was dominated by:

(1) The Tolbooth, dating from 1394, but rebuilt in 1615 and nowadays largely concealed by the frontage of the Town House, built in 1867-72 in Flemish-Gothic style.

(2) The New Inn built by the Freemasons in 1755, visited by James Boswell and Dr. Johnson in 1773. The Freemasons had their Lodge on the top floor, hence the adjacent Lodge Walk. The New Inn was replaced by the North of Scotland Bank, later the Clydesdale Bank, built in 1839-42 as the corner-piece of Castle Street and King Street, and now a pub named after its illustrious architect Archibald Simpson.

(3) Pitfodel’s Lodging of 1530 was the town house of the Menzies family of Pitfodels, a three-storey turreted building, the first private residence in Aberdeen to be built of stone after its predecessor was destroyed by fire in 1529. The Lodging was demolished in 1800 and replaced the following year by the premises of the Aberdeen Banking Company, from 1849 the (Union) Bank of Scotland.

The power and influence of the Menzies family, who were Catholic and Jacobite, was in decline by this time and their old motte-and-bailey castle at Pitfodels, a stone-built tower-house, was in ruins. The associated earthworks were still to be seen at what became the entrance to the Norwood House Hotel until the 1970s, but not much is left there now. The family moved to Maryculter House in the early 17th century. In 1805 John Menzies put the lands of Pitfodels up for sale (also those of Maryculter six years later) and in 1806 purchased 37 Belmont Street (now Lizars opticians). This house had been built in the 1770s and thus pre-dates Belmont Street itself, which was laid down in 1784, well before Union Street.

It is from this house that Mary Queen of Scots is believed to have witnessed the beheading of Sir John Gordon in 1562

In 1831 John Menzies donated his mansion and lands at Blairs to the Catholic Church for use as a college and moved to Edinburgh. He died there without heirs in 1843, the last of the Menzies dynasty, receiving a spectacular Catholic funeral.

Until about 1715 the deceased members of the Menzies family were buried in ‘Menzies Isle’ within St Nicholas Kirk, thereafter in the Kirk-yard. Latterly they were buried at the ‘Snow Kirk’ in Old Aberdeen, just off College Bounds, where the Menzies family grave remains prominent.

(4) Earl Marischal’s Hall dating from about 1540 was next to Pitfodel’s Lodging on the south (harbour) side of the Castlegate. This was the town house of the Keiths of Dunnottar, the Earls Marischal. It had been the Abbot of Deer’s town house but became the property of the (Protestant) Keiths following the Reformation. It consisted of a group of buildings surrounding a central courtyard with gardens attached. It is from this house that Mary Queen of Scots is believed to have witnessed the beheading of Sir John Gordon in 1562 following the defeat of the Gordons of Huntly at the Battle of Corrichie.

Earl Marischal’s Hall was purchased by the Town Council and demolished in 1767 to allow ‘the opening up of a passage from the Castlegate to the shore (or harbour) and erecting a street there’, that being Marischal Street. Before then there had been no direct route from Castle Street to the Quay, and the growth of trade at the harbour made a new street absolutely necessary. Marischal Street was (and still is) a flyover, possibly the first in Europe, vaulting Virginia Street by means of ‘Bannerman’s Bridge’. It was also the first street in Aberdeen to be paved with squared granite setts, the first street of the new, post-medieval Aberdeen and it is the only complete Georgian street remaining in Aberdeen today.

5) Broadgate or Broad Street was the main street of Aberdeen according to Parson Gordon’s map of 1661, lying as it did between the main route north, the Gallowgate and the main (and only) route south via the Green, Windmill Brae and the Hardgate. The old town of Aberdeen never had a High Street as such, probably because St. Katherine’s Hill stood in the way of the most obvious route for a High Street, from the ‘Mither Kirk’ of St. Nicholas to the Castlegate.

A previous resident of Broad Street was the young George Gordon, later Lord Byron. He was born in London in 1788 and was named after his maternal grandfather George Gordon of Gight Castle in Aberdeenshire. The child was brought to Aberdeen in 1790 by his mother Catherine Gordon, after her worthless husband ‘Black Jack’ Byron, had dissipated her inheritance, resulting in Gight Castle being sold to the nearby Gordons of Haddo.

The Castlegate became squalid and dangerous and was notorious for the number and brazenness of the prostitutes

Mother and child lived in lodgings at No.10 Queen Street then moved to No.64 Broad Street. Young George attended the Grammar School at its original location in Schoolhill until 1798, when he inherited his father’s brother’s title and returned to England to continue his education at Harrow, where he was bullied on account of his club foot and Scottish diction.

Castlegate decline

The construction of Union Street from 1801 and the development of the ‘New Town’ westwards of the Denburn encouraged the wealthy and fashionable to migrate in that direction, and the old or medieval town deteriorated throughout the 19th century. The Castlegate became squalid and dangerous and was notorious for the number and brazenness of the prostitutes, who catered for the soldiers in the Barracks and the seamen from the harbour.

The congested old streets and wynds became filthy, infested, stinking and diseased. The courts and closes branching off the Gallowgate were described in 1883 as the dingiest and most unwholesome of any British town. Across the whole Burgh there were still in 1883 some 60 narrow lanes and 168 courts or closes of a breadth of seven feet at most.

The average number of inhabitants per house was reckoned at 14.8 persons. In the St Nicholas Parish the average was 16.8 persons per house. This level of congestion and overcrowding arose because the city’s population was expanding much faster than its geographical boundaries; from 26,992 persons in 1801 to 71,973 in 1851 and to 153,503 in 1901.