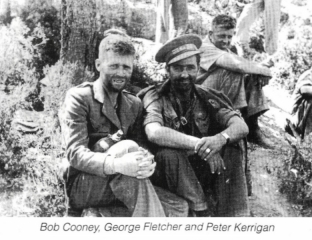

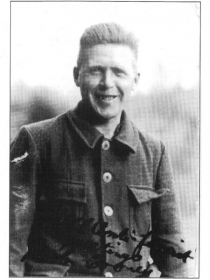

Neil Cooney, Aberdeen City Councillor for Kincorth/Loirston, shares his Uncle’s life story with Voice readers. Bob Cooney grew up all too familiar with loss and hardship during that period when the concept of Socialism was also growing up. The saying goes, ‘Those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it.’ In the present day, Bob’s situation in the late 1920s has a powerful echo today:

“The traditional Treasury answer was that the problems would eventually sort themselves out; we simply had to weather the storm. In the meantime budgets had to balance and we had to save our way out of the crisis. This meant cuts in spending, cuts in benefits and cuts in public sector salaries”.

And so the story – in three parts – begins.

Bob Cooney was born in Sunderland in 1908, the seventh child of an ambitious Aberdeen family. His father, a cooper, had moved around the country chasing promotion. Less than two years previously the sixth child, George (Dod) had been born in Edinburgh.

Father was a fit man, an athlete, a champion swimmer, winner of the exhausting Dee to Don Swim, a water-polo player of some note, and good enough on the bowling green to win the Ushers Vaux Trophy in 1903.

It therefore came as a total shock when months later he died suddenly of pneumonia contracted on the way home from a funeral in Aberdeen.

His widow Jane had just turned 37; she was left with seven children, none of whom were of an age to earn. It was at a time when welfare was only beginning to be debated: it was still a case of all words and no action. The right of the governing Liberal Party and the Tory dominated House of Lords both shared the view that welfare would destroy the moral fibre.

She had little hope but take her brood back to Aberdeen where at least the support of relatives could tide her over the next few difficult weeks. They came by boat from Newcastle. Rooms had been found for them in Links Place: there they were soon to be burgled of what little they possessed. The children were enrolled at St Andrews Episcopal School. Jane got a job cleaning HM Theatre, with extra evening work as a dresser for the big shows. She was fiercely independent and ruled her brood with a rod of iron. Times were tough and she had to be tough to survive. Bob and Dod, in particular, often tasted the back end of the hairbrush.

In time, the family moved first to Northfield Place, then to Rosemount Viaduct where Jane, although very frail but would not admit it, was employed as a caretaker of the five blocks of flats. This entailed a lot of scrubbing and polishing, helped by the children as they grew up. The family stayed in Rosemount Viaduct until the 1950s when medical needs provided them with a move to Manor Drive; by then her daughter Minnie was virtually immobile.

Schooling at St Andrews Episcopal was fairly basic, but the children gained the necessary skills of literacy and numeracy to fit them for future life. Bob and Dod were both clever enough to reach the top of the class at eleven: there they remained until they left school at 14. The boys cleaned the school before and after classes. Each of them also served in the choir, as reluctant volunteers.

Bob took over Dod’s Watt and Milne job at the age of twelve, fitting it in before and after school

They were not alone in their poverty. One fellow pupil was tempted to steal a sausage from a Justice Street butcher’s display. Unfortunately, for him, it was but the end of a huge link of sausages: he was quickly caught and brought to justice – some six lusty strokes of the birch: he bore the scars for the rest of his life.

A young girl classmate remained barefoot even in the height of winter. A teacher bought her sturdy boots, which were later thrown at her by an angry father who declared that if his daughter needed boots, then he would provide them. Schooling was never boring. Bob, being younger, was let out of school before Dod, but had to wait for him to escort him home. Bob even in his youngest days was adventurous enough to prove his own capacity to see himself home: his early homecoming was enough to get them both a hiding.

The children were all given a trade. Matthew never qualified: he died in his teens. Young Jean went into service before training as a nurse: she provided the younger children with the tender loving care that her mother was unable to do. She never married, neither did Minnie who became a seamstress and spent much of her life cruelly crippled.

Tom was a carpenter; he was to die very young, leaving a young family. Sandy was a French polisher in the shipyards, he remained a bachelor, he spent his weekends cycling and hostelling, and he loved books and music and was an expert in Esperanto.

Dod spent a few months as an errand boy for Watt and Milne before becoming an apprentice watchmaker with Gill’s of Bridge Street before moving on to the Northern Coop, where he worked until he retired.

Bob took over Dod’s Watt and Milne job at the age of twelve, fitting it in before and after school. His early morning job consisted of cleaning the plush carpets, usually on his hands and knees; after school he was the delivery boy carrying hatboxes to the West End. On leaving school, Bob was apprenticed to a pawnbroker.

He never believed that the ruling class would give in to mere arguments

The pawnshop was an alternative to debt. It provided the coppers required to see you through the week. Men’s suits would go in on a Monday morning and be redeemed on Saturday morning, still in the neat brown paper parcel.

If the suit was needed through the week for a funeral, then the neat parcel was filled with old newspapers. Bob allowed himself to be easily deceived. He had many a laugh with the customers but he hated the pawnshop system.

Poverty was beginning to anger him. He was listening to the debates at the Castlegate; it was his finishing school. He became a Socialist, and then he took the next step by becoming a Communist. He never believed that the ruling class would give in to mere arguments. It needed a revolution and that required the active participation of the people.

Stubborn, Strong and Single Minded

Bob became a speaker out of necessity – there was no one else around to do the job. He became a speaker in his teens, honing his technique over the years. His mother didn’t like his political involvement, and firmly drew the line at his ambitions as a speaker. He had to stop or get out of her home – he got out for a while to escape the unbearable tension. His antics, as she saw them, were taking away from her the respectability that she had earned the hard way. She had already followed his route through the streets, scrubbing the slogans he had chalked on the pavements. How could he let her down like this?

In many ways, Bob took after his mother. Both could be stubborn, strong and single-minded. Both set themselves very high standards. Jane was perplexed that Bob had gone down the route that Sandy and Dod had already chosen. Dod was receiving letters from the House of Commons, and although she managed to intercept some by following the postie, much to her horror she discovered his dark secret.

She worried that if her employers found out, she could lose her job and become homeless.

The TUC leadership lost touch with the rank and file. It was a huge disappointment to the Aberdeen Socialists

Why, after the hard years of struggle to bring them up, did they disgrace her in this way?

The girls were good church-going Christians, but the boys were meddling in Left-wing politics. She was black affronted.

She was also scared: political tempers were running high in 1926, the year of the General Strike and Churchill’s “British Gazette” was deliberately playing the Red Menace card. “Reds under the beds?” she seemed to have a house full of them.

The General Strike was a let-down to the idealists of the Left. They felt that they had the potential for power — until the TUC chickened out and called off the strike. It drove a wedge between the Far Left and the Left; it was a defining moment that the broad kirk split apart.

Old comrades now put up candidates against each other. The TUC leadership lost touch with the rank and file. It was a huge disappointment to the Aberdeen Socialists who had completely controlled the city. Nothing moved without a permit or without the strikebreaking students being stopped. Aberdeen even produced its own strike newspaper. The Tory government controlled the national media with Churchill thundering about the ‘red menace’ in the “British Gazette”, and a procession of Cabinet ministers hogging the microphones of the BBC.

After the Strike collapsed, the jubilant Tories extracted every ounce of revenge. New anti-Trade Union legislation was rushed through. The Unions were to be further weakened by the Depression.

Unemployment had been high since the Great War; our heavy industries suffered badly from foreign competition. We couldn’t compete with the price of Polish coal, our factories were screaming for re-investment. Even British companies chasing bargains abroad bypassed our shipyards. Chancellor Churchill’s 1925 decision to go back to the Gold Standard was a mistake of the highest order, making our exports far too expensive.

This meant cuts in spending, cuts in benefits and cuts in public sector salaries

The killer blow came with the shockwaves of the 1929 Wall Street Crash. Unemployment soared and the Insurance Scheme could no longer self-finance. The traditional Treasury answer was that the problems would eventually sort themselves out; we simply had to weather the storm.

In the meantime budgets had to balance and we had to save our way out of the crisis. This meant cuts in spending, cuts in benefits and cuts in public sector salaries.

In 1931, the Labour Cabinet split over a proposed cuts package and resigned, leaving the renegade Ramsay MacDonald (“Ramshackle Mac”) to hold on to power by forging an alliance with Baldwin’s Tories in the National Government. Bob slated Labour for abandoning the poor. The Communist candidate in Aberdeen North in 1931, Helen Crawford, gave Wedgewood Benn a torrid time in the ensuing election campaign that saw the largely anonymous Conservative Councillor Burnett of Powis romp home in Aberdeen North, a seat that had been a Labour stronghold for the last five elections.

The National Government produced a vicious cuts package that provoked a wave of anger that culminated in a rather polite naval mutiny at the Invergordon base. Among the 12,000 mutiny participants were Sam Wilde and Bill Johnstone, who later served with valour in Spain. The mutiny triggered a run on the banks and forced the Government, in panic, to come off the Gold Standard and devalue. It was the best piece of economic management that they ever produced.

Next week in Aberdeen Voice, Cllr. Neil Cooney continues his account of Bob Cooney’s amazing and inspirational life. In part 2 we learn of Bob’s political education, encounters with Mosely’s Blackshirts, and the Spanish Civil War.