A recent Aberdeen Voice piece looked at salmon fishing issues and Montrose-based USAN. Seals were shot in Gardenstown, confrontations occurred between Sea Shepherd, hunt saboteurs and USAN, who operate salmon nets in the Crovie area. Animal welfare organisations condemned USAN’s activities.

USAN’s George Pullar invited Suzanne Kelly out on the boat to experience first-hand a typical day on the water taking salmon. Pullar wanted to explain his operations and his difficulties; this is the story of how the day unfolded. By Suzanne Kelly.

It is a pleasant afternoon when George Pullar collects me from the Montrose train station for my visit. Montrose station by the way is adjacent to wildlife habitat, the Montrose Basin.

This is a highly valued local nature reserve where fishing and wildfowling are permitted leisure activities.

I am admittedly the sort of person who only wants to shoot wildlife with a camera. I wonder what sort of day I’m in store for.

We arrive at the USAN operations south of Montrose. A floating net is currently hung up on the grounds of the Pullar property; the cage is, I am struck by its huge size.

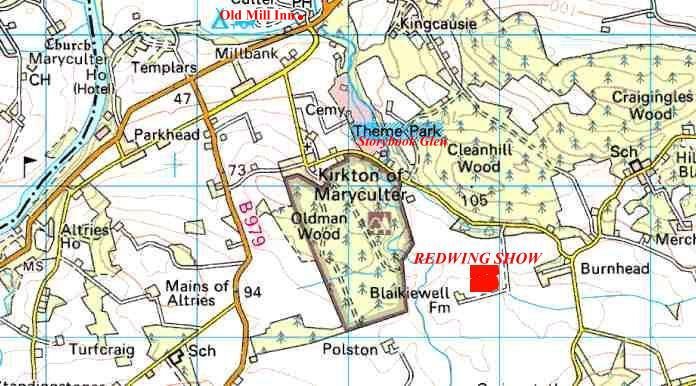

USAN operates in a number of areas around the east coast of Scotland; USAN advise they purchased fishing rights as private heritable titles on a willing buyer/willing seller basis, as with all the rights they own, and are keen to point out they have not operated nets in the Ythan Estuary area and state that they have not shot any seals. However, anglers concerned about salmon stocks and animal welfare groups are concerned about seals in the area, and George has told me that if a seal persistently steals from any of his nets, he wants to have it shot. The local anglers, who have contributed towards maintaining salmon stocks, are ‘dismayed’ at the news of USAN operating in the area.

USAN was also granted a licence to shoot some 100 seals; after public outcry, the company was widely quoted in the press as saying it will not take seals. But George Pullar is adamant seals which interfere with the nets will be shot.

The Scottish Government via Marine Scotland issues licences for killing grey and common seals to the farms and the netting fisheries. Their 2013 figures brag that ‘only’ “105 seals have been shot across 216 individual fish farms and 169 seals across over 40 river fisheries and netting stations during the third year.” and that “licensees are only shooting seals as a last resort.”

Pullar and I get onto the subject of hunting in general; there are a few nice looking dogs on the property. Pullar is not interested in shooting deer or rabbits for fun or sport; he says his shooting is confined to protecting his nets and his fish from seals.

We walk down a path to the bothy, where we are joined by others including George’s son. Everyone puts on protective gear and a life vest, and we go aboard the motorised boat. Eight large fish packing boxes are aboard, empty. They will soon almost all be filled with salmon, large and small.

The motorboat goes to the netting areas past ‘Elephant Rock’ a local landmark. We pass George’s cliff top house.

He tells me that hunt saboteurs, wearing balaclavas have not only been monitoring USAN’s activities on the water, but have also been watching his house. Unsurprisingly, the police are monitoring the hunt saboteurs, and George tells me that anti-terrorism police are also involved and are interested. Pullar is concerned for his family and his business.

We arrive at the first net, a floating cage. The fish go into the wide opening, and the further in they go, the more trapped they become.

The crew grab one side of the net from the side of the boat; they begin to haul their catch. Then each man grabs a small wooden club. Suddenly the bottom of the boat is filled with salmon, struggling for oxygen. They are terrified, they are gasping; they flap helplessly. Small fish, large fish, all are clubbed to death on the head as swiftly as the crew can manage.

We repeat this process some 14 times more; I’ve lost count.

My first impulse is to put the salmon back in the water and save them; this is of course impossible and whether or not I am there, the fish will be killed. The small ones look particularly helpless to me; the large ones are nothing short of majestic. But I must report that the killing of these animals is accomplished quickly.

I think of the many ways fish and meats are produced; I think of the farmed salmon.

If animals are to go into the food chain, it is better that they have a free, natural life and a swift end to my way of thinking.

George agrees with me readily as to the treatment meted out to farm animals; if I’ve understood him correctly he has seen a chicken processing plant in operation.

I want to discuss his relatively swift despatching of the previously wild salmon as opposed to how caged salmon live.

Farmed salmon are kept in relatively small pens, where in the wild they would have covered wide open sea and river areas. Farmed fish are fed a cocktail of drugs; they are prone to sea lice, which cause great pain as they eat the farmed salmon’s flesh, often to the bone. And there is powerful evidence that the areas under these cages become barren; I spoke to a diver who equated the area under a salmon cage he’d seen with the Empty Quarter desert.

George asks me if I eat fish; I say no. He asks if I eat any meat; I say I’m vegetarian. I do say though that from what I know and what I’ve seen of meat production, I cannot really argue with the speed in which the salmon are killed on his boat.

After they are killed, they are tagged as wild Scottish salmon with a tag carrying the USAN logo.

The number of fish in each net varies. Some have only 2-3 fish. Some have dead salmon and a fair number of jellyfish. I only see a few types of other fish in the nets; a mackerel, and Pullar points out some herring. He tells me in effect there are plenty of fish in the sea.

That may be so, but there are some serious concerns being expressed about the number of wild salmon to be found in the rivers. The anglers also support local businesses and bring money into rural economies. The anglers of late are hardly catching a thing. Pullar today has taken at least 50 salmon, and while this number can vary greatly, he says they clear the cages twice a day.

Some reports state that total salmon catch figure decreased from 500,000 in 1975, to 100,000 in 2000. Today, anglers in Scotland’s rivers are hardly getting any salmon at all. Andrew Graham-Stewart, Director of the Salmon and Trout Association (Scotland) said:

“This is a very bad year for salmon. Numbers returning to the coast from their marine migrations appear to be well down. Very few are entering their rivers of origin. This situation is exacerbated by the dry weather. Given the lack of flow in the rivers fish tend to wait in coastal waters where they are highly vulnerable to coastal nets – such as those operated by USAN.”

USAN’s nets south of Montrose are a classic “mixed stocks fishery” – taking fish destined for many rivers between the Tay and the Spey. Radio tracking by Marine Scotland of fish caught south of Montrose shows conclusively that some are destined for the Dee.

USAN is answerable to The Esk District Fishery Board for its operations. There are conflicts in legislation – ‘leaders’ are meant to be removed from the floating nets at specific times – but the rules take no account as to prevailing weather conditions. USAN has fallen foul of these laws, and is seeking to change them.

I haven’t seen a seal all day; and on previous boat trips down the coast, I have almost always seen some.

I wonder why there are none at all in such an area as George’s nets are. I ask him about seals.

“If a seal only comes to the nets once, it’s not a problem. But if the same seal comes back, then (it will be shot). These are my fish (the ones in his nets)”

George also seeks to assure me that the police were happy with his having guns and how they were stored in Gardenstown and Crovie. This was an issue touched on in a previous article.

I know that Marc Ellington, who owns the lands in Gardenstown and Crovie has formally forbidden USAN to shoot from his lands. As I understand, it is illegal to shoot from a boat (for rather obvious reasons; the water is hardly a stable place from which to aim).

Pullar tells me that his company is working with developers to improve devices which use sound to repel seals (he says not all seals are susceptible to the noise such devices emit). He points out to me the steel bars he has installed on some of his floating cages to prevent seal access to the salmon, and netting in use on other cages to prevent seal access as well.

George feels that the press is ignoring efforts he is making with the university and developers to keep seals out of the nets and therefore out of the equation which is one of the main objections people have to USAN’s operations – the shooting of seals.

It is clear to me that if USAN were to market itself as a company that took wild salmon without ever harming any other wildlife – it would be pleasing clients and people concerned with the environment. Even if the company took fewer fish as a result, it seems clear to me people who care about wildlife (even if they eat salmon) would be willing to pay more for a product that didn’t involve shooting other creatures.

Last year a seal was shot in Gardenstown in front of two newly-arrived tourists who had rented a cottage.

They promptly packed and left. The police’s investigation into the shooting – which took place without the landowner’s permission – fizzled out.

USAN makes no secret of the fact they will shoot the animals if they interfere with the nets.

USAN made a statement to government which sets out its arguments – theirs is a heritable business in a sector which they see as being persecuted by angling interests.

In the document USAN discusses the Close season and the fact anglers get a longer period in which to fish. USAN employs some 14 people, and support the local economy.

But when USAN states:

“It is reprehensible for us to have to survive on reduced fishing time, where there is no threat to salmon stocks.”

– it is clear that this conflict is about more than seals; it is also about conflicting opinions on how much salmon stock should be taken, and what the future holds for the wild salmon population.

It’s A Living Thing.

Pullar wants to provide for his family and to pass his business on, just as his father has done. We talk about what I do for a living (I’m a secretary when I’m not writing for Aberdeen Voice, by the way, as well as a painter and craftsperson, and a few other things). My skills are transferable; I’m also always trying to learn new skills.

I wonder perhaps if the Pullar business model could benefit from some diversification – adding wildlife tours, education, etc. to the business model.

The world is rapidly changing; in Aberdeen the talk often turns to what will happen when oil runs out. It is entirely possible that the salmon population is dwindling – overfishing (arguably), pollution, climate change are driving changes which can’t be beneficial for any wildlife. Pullar could always find other ways to work; he doesn’t want to and by law he doesn’t have to.

I think of the seals. They have to eat what they find – there is no choice for them. Do we really have to take as many fish as we do Experts advise that many dead seals are found not to have salmon in their stomachs when examined. But if the definition of ‘vermin’ is one species going after the food needed by another species – are the seals the vermin – or are we?

On our way back to the Pullar bothy, three hunt saboteurs are sitting on the shoreline. They wear balaclavas and are filming us. The boat goes closer; George is filiming them; they film George and I am filming them both. It is a sureal moment and soon we are back to the Pullar property.

We return to shore; the boxes which had filled up with fish are put on a forklift, and taken to the bothy’s packing plant. On my way back to George’s car, I meet his father. Three generations of the Pullar family are engaged in the business.

My Closing Thoughts.

I leave with a bit more insight into USAN’s operations and its issues, and with some hope that a way will be found to stop shooting any seals.

It’s clear to me they aren’t the only ones shooting seals. Once again I find myself wondering if the Scottish Government and its environmental bodies SNH and Marine Scotland are more interested in money and politics than in the state of Scotland’s ecology and the biodiversity of the future.

I think that if I were a hunt sab, or animal rights activist, Pullar would be of less interest to me than the people involved in industrial farming on land and on sea and the institutionalised cruelties entailed.

I question the tactic of hanging around someone’s house wearing a balaclava; the hunt sabs didn’t make very many friends in Gardenstown either; they were asked to leave.

Intimidation is a tool, but working together to find solutions in a less confrontational manner should be preferred. Pullar says he’s working on ways to keep the seals away from the nets; I will follow his progress and encourage it.

I also leave with renewed determination to remain a vegetarian, and may perhaps go vegan.

But mostly, I’m thinking of the seals, deer, geese and the habitats that are being destroyed before my eyes since I moved to Scotland. That for me is the bigger picture, and until someone in power decides that money is less important than halting urban sprawl and encouraging biodiversity in deed rather than in words, I believe we are all heading for trouble.

Do not watch the following video if seeing fish being clubbed will upset you. Do not assume that is meant to show up USAN’s killing. It will show everyone who likes their smoked salmon exactly where it comes from. I recommend watching it while bearing in mind what is going on to get the low-cost chicken, lamb, pork and beef onto your table, which would be far more upsetting to watch.

- Comments enabled – see comments box below. Note, all comments will be moderated.