By Alex Mitchell.

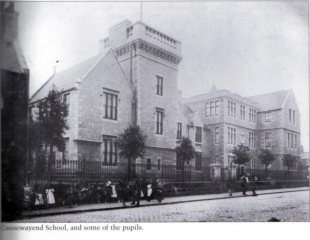

Causewayend School was one of the many handsome and impressive Victorian granite Board schools created in Aberdeen for the fast-expanding city population of the later 19th Century. In fact, Causewayend was more handsome and impressive than most such schools, being designed by William Smith in 1875 and with a later Baronial-style keep by William Kelly.

But the school has now closed because of the declining number of children resident in its catchment area of Mounthooly-Gallowgate-West North Street. Not for the first time, we are struck by the sheer folly of the systematic removal of population and community from this (and other once-thriving and central neighbourhoods) through demolition of older tenement housing and its replacement – if at all – by tower-block flats, soon found to be unsuited to the needs of families.

The thing is that Mounthooly-Gallowgate ought to be what estate agents would describe as ‘a sought-after urban-village locality’; central, historic, characterful, surrounded by vistas of steeples, towers and spires and within walking distance of M&S. But its almost entirely public-sector housing provision – and that largely in the form of tower-block flats – effectively excludes would-be owner-occupiers, the ‘mortgage paying classes’, as well as those with families to raise.

The consequence is that the area contains relatively few middle-class families, but disproportionate numbers of poor and/or elderly people. Those blocks which are hard-to-let will also typically feature high concentrations of benefits claimants, the unemployed, single guys just out of the services or prison, alcoholics, drug addicts and the mentally ill.

A functioning community needs a more representative social mix than this; the better-off as well as the poor, high-achievers as well as under-achievers, people with scarce and marketable skills, professional expertise and entrepreneurial talent. The local schools, like the canaries in coal mines, give the early warnings that a community is in distress, being especially vulnerable to a downward spiral of local disadvantage, poor test and exam results, pupil withdrawal, declining enrolment and so on.

The current pre-occupation as regards housing provision is with the supply and availability of ‘affordable’, i.e., low-cost, housing. It may seem perverse to say so, but what Mounthooly-Gallowgate really needs is more high-cost housing, such as would attract the mortgage paying classes back to this locality. Housing costs in any neighbourhood tend to reflect the earning-power of local residents. In the U.S. context, you have to pay a high rent, or house price, to live in, say, Manhattan, because you are surrounded by high-earning people. (The characters in Friends couldn’t possibly afford to live there!) You would pay a lower rent or price to live in Brooklyn or Queens, because there you would be surrounded by lower-earning people.

Low-cost housing reflects the low earning power of local residents, their lack of marketable skills and expertise and/or entrepreneurial flair, possibly compounded by, or attributable to, low educational attainment, poor physical and mental health, drug and alcohol abuse and criminality. A failed or collapsed local economy, such that decently-paid jobs are simply unavailable, might also come into it; but that has not been the context here in Aberdeen for some decades past.

The World Bank investigated the underlying causes of the relative wealth or poverty of different countries in 2005. They concluded that: “Rich countries are rich largely because of the skills of their populations and the quality of the institutions supporting economic activity”.

Much of this is attributable to intangible factors – the extent of trust amongst and between people, an efficient judicial system, clear property rights and efficient government. On average, the ‘rule of law’ accounts for 57% of a country’s ‘intangible capital’, whilst education accounts for 36%. But whereas Switzerland scores 99.5% on a rule-of-law index, and the USA 91.8%, Nigeria’s score is a pitiful 5.8% and Burundi is worse still at 4.3%. Some countries are so badly run that their intangible capital is actually shrinking. The keys to prosperity are the rule of law and good schools; but through rampant corruption and failing schools, countries like Nigeria and Congo are destroying the little intangible capital they possess, and are thereby ensuring that their people will be even poorer in the future.

There are too many parts of Britain where no-one in their right mind would think of starting a (legitimate) business enterprise

What is true of countries in the global context is also true of regions, cities and towns within a country and even of neighbourhoods within a city or town. The rule of law, i.e., crime-prevention, and a functioning education system are basic pre-conditions for industry, investment and employment; not least because decision-takers are picky about where they live and the schools their children attend.

There are too many parts of Britain where no-one in their right mind would think of starting a (legitimate) business enterprise, and where almost no one does.

Even in the relatively prosperous context of Aberdeen, there are neighbourhoods where the trend is all-too observably one of business closures and withdrawal rather than start-ups and expansion, and for all-too obvious reasons; a collapse of law & order, rampant criminality, and a lack of relevant skills and, consequently, of spending-power amongst the local population and labour force. As the World Bank concludes, the solutions are (a) the rule of law, and (b) efficient education systems.

In the local context of Aberdeen neighbourhoods like Mounthooly-Gallowgate, the immediate or quick-fix solution is probably that of improving the social mix by making available a wider range of housing types – private-rented, owner-occupied, detached/semi-detached or at least maisonettes/terraced, rather than having only high-rise blocks of Council-owned flats. However, closing schools like Causewayend and nearby Kittybrewster seems like a seriously bad move.

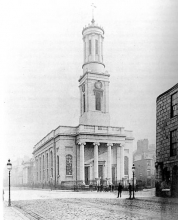

The theme of the emptying inner city came to mind on a recent visit to Aberdeen Arts Centre, which has long occupied the former North Church, No. 33 King Street.

This splendid 1830 Greek-Revival building by John Smith was positioned so as to be visible and conspicuous from almost all angles, central to the whole area. Yet it is surrounded by streets, once vibrant with people, shops and businesses, which now contain little or no resident population; the south (town) end of King Street, Queen Street, East/West North Street and Broad Street.

It is as if the planners had set out to ethnically cleanse the whole area of humanity. That has certainly been the effect of past planning decisions, even if not the intention.Even on a sunny Saturday afternoon, there is not a soul to be seen in any direction. We are reminded of the bleak post-war Vienna depicted in the film The Third Man, its population dead or dispersed to the four winds.