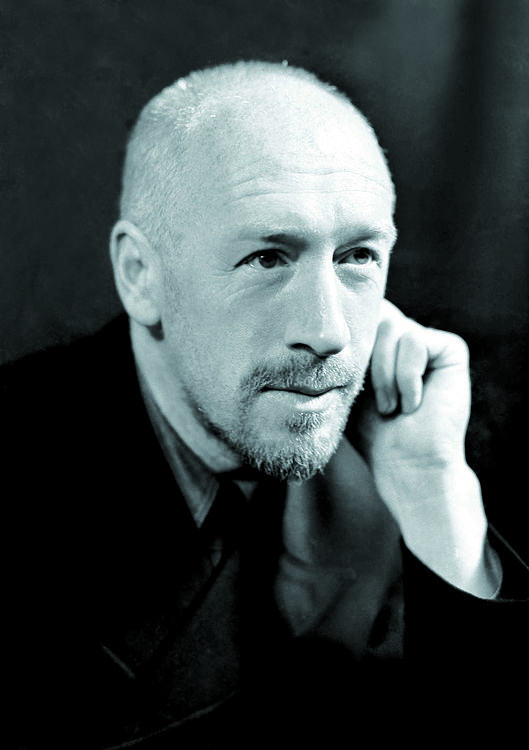

Born in Southsea and from a naval family, Peter Anson (1889 – 1975) took a keen interest in ships and seafaring from an early age.

Initially he sketched from photographs but at age nine, during a family holiday at Robin Hood’s Bay, Peter began drawing the Fifies’ and Zulu drifters beloved by his mother, a Scots born water-colourist. Peter attributed his status as a ‘Domiciled Scotsman’ to her strong maternal influence. She died when he was fourteen and from this point on, his naval officer father began to have more input.

On one memorable occasion Peter found himself, age 15 alongside his dad, on-board the cruiser HMS Argyll – sister ship to the ill fated Hampshire which went down off the Orkney’s in 1916 with Lord Kitchener, of ‘YOUR COUNTRY NEEDS YOU’ fame, on board.

This was his first experience at sea in a warship and he writes that he did not enjoy “the terrific noise of guns firing” during a naval exercise in the Bay of Biscay. Despite this, he was by now smitten by seafaring and felt himself a hardened sailor following this experience.

Private tutoring followed and in his late teens Peter enrolled at the Architectural Association School in London’s Westminster. Even here however he found that he couldn’t resist maritime subjects. He obtained a sketching permit which allowed him to wander at will, sketchbook in hand, around London Docks. Wapping, Blackwall and the Isle of Dogs became favourite haunts and Thames river traffic became his subjects.

By 1906 Peter was in touch with the Anglican Benedictine community on Caldey Island near Tenby and despite family pressure to follow an architectural career found himself drawn to the monastic life.

In 1910, he tested his vocation as a monk. Following an initial two weeks on Caldey Island he decided, at age 20, to join the Community. Many years later he writes:

“I might be giving up the world, but this would not involve abandoning the sea … I don’t think that I could have faced the latter sacrifice! It would have been too much to ask!”

For the next decade, Caldey Island became his home.

Six miles in circumference and less than a mile long, the island had been home to monks from early Celtic times. In 1906 it was purchased by a Yorkshire based community of Anglican Benedictine’s.

It is a place of jagged coastal rocks, Atlantic storms and red sandstone cliffs and it was here that Peter became firm friends with Aelred Caryle, his monastic Superior, who helped him realise the Apostolate of the Sea – a mission to attend to the moral and spiritual needs of those who go to sea in ships.

An article on the subject penned by Peter appeared in The Catholic newspaper ‘Universe’ and soon letters began to arrive from all parts of the world endorsing his view that the spiritual welfare of seafarers in general went largely uncared for. One correspondent commented that:

“the mercantile marine have no chaplains and the priests in seaport towns are too overburdened with work already to give ships much individual attention”.

The Catholic Times soon took up the issue and in 1920 the Vatican newspaper Osservatore Romano published a condensed Italian translation of Peter’s article. Peter had by then, as always, moved on to fresh projects. In what he later realised was an attempt to escape from monastic life and a return to the maritime world, Peter asked permission from the Abbot of Caldey to make a survey tour of the seaports of the UK.

He made many sea journeys during this period and travelled from the Shetlands to the Scillies.

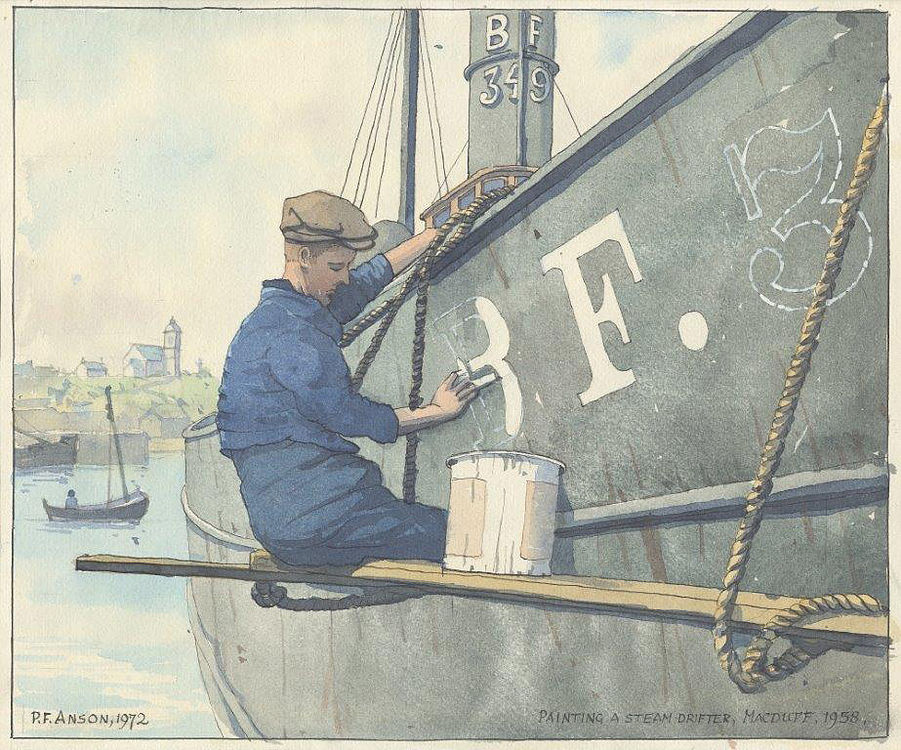

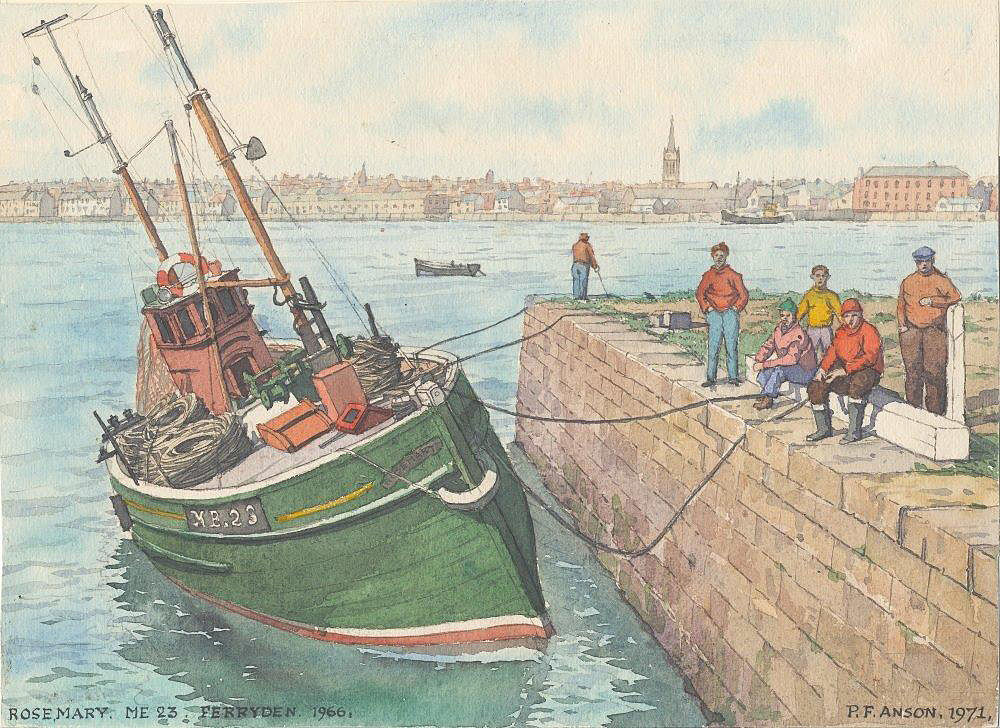

He sailed in dirty colliers and smoke stained steam trawlers and at one point spent so long in an Italian cargo vessel that he almost forgot how to speak English. In Buckie he found a fleet of over a hundred brightly painted steam drifters and wondered why no artist had ever painted the confused mass of funnels, rigging and masts.

In Aberdeen he observed:

“big dirty, untidy vessels which were a stark contrast to the tidy vessels of the Moray Firth.”

Everywhere he travelled he met clergy who had largely given up on ministering to ships and abandoned seafarers whose spiritual needs were left largely neglected.

The question of what could be done for Catholic seafarers had been the catalyst for the setting up of the Apostleship however when Peter moved to Portsoy and then to Macduff in the 1930’s it was soon apparent to him that the crews of the herring drifters were made up of men from various persuasions.

Methodists, Baptists, Episcopalians and Presbyterians; Brethren, Salvation Army and Catholics were all happy to discus both the state of the tide with him and debate the finer points of infant baptism or the mysticism surrounding the crucifixion.

The painting and the sketching carried on throughout this period, as it did indeed throughout his long life. The Apostleship of the Sea had become an international affair complete with annual congresses attracting delegates from up to 14 countries. By 1936 however, Peter had withdrawn from the official life of the organisation.

Indeed he took great pleasure in the fact that on the occasion of the Congress’s meeting to honour his colleague Arthur Gannon’s 17 years of devoted work with the award of the ‘pro Pontifice et Ecclesia’ he was pointedly busy making a drawing of a Dutch motor cruiser in Banff harbour whilst chatting amiably with its crew.

Indeed he took great pleasure in the fact that on the occasion of the Congress’s meeting to honour his colleague Arthur Gannon’s 17 years of devoted work with the award of the ‘pro Pontifice et Ecclesia’ he was pointedly busy making a drawing of a Dutch motor cruiser in Banff harbour whilst chatting amiably with its crew.

Peter had in fact resigned his position as the Apostleship’s Organising Secretary in about 1924 due both to health concerns and the feeling that he had visualised the society much as he would visualize a drawing or a piece of writing.

Once the piece was completed, he simply wanted to get on with the next project.

Travels:

Further sea journeys followed. Brittany, Vancouver and a much needed pilgrimage to Assisi were just some. In 1938 he published The Caravan Pilgrimage, an account of his year long ‘Pilgrim Artist’ journey by horse drawn caravan from Datchet by the Thames around Scotland’s North East coastline and back.

For many years Peter had been contributing a weekly series of drawings to the Catholic newspaper, The Universe featuring Roman Catholic churches around Britain. This work involved constant travelling by train; he hated road travel, which he found exhausting. One day he simply decided to divest himself of his copies of both Bradshaw and the ABC Railway Guide and purchased a horse drawn caravan.

Since he knew little about horses his next move was to advertise for a travelling companion who did. Out of almost 200 applications he chose a young Yorkshire-man by the name of Anthony Rowe who, alongside a lifetimes experience amongst horses, was a qualified farrier.

Along with horses, Jack and Bill, the pair set off on a year long journey around Britain, sketching churches and meeting folk along the way. Both Anthony and Peter recorded the journey and both published journals of the trip. Around 60 of Anson’s illustrations of the pilgrimage appear in the book of the tour including sketches of St Peter’s in Buckie, St Mary’s in Portsoy and St Thomas’s in Keith.

Along the way, Jack and Bill enjoyed the privilege of overnight grazing in, amongst many unusual locations, the grounds of Huntly Castle and Buckie FC’s football park.

Harbour Head Macduff:

In 1936 Peter moved back to Scotland. He had lately been living in Norfolk but had become weary of what he called:

“the Church of England in it’s most traditional and un-exciting manifestations.”

He had an intimate knowledge of Scottish ports having previously visited most of the forty or so parishes, including the Orkney’s and Shetlands which then made up the diocese of Aberdeen and knew many of the 50 or so secular priests who served up what he termed:

“an undemonstrative type of Catholicism.”

The Aberdeenshire and Moray coastline became his home for the next two decades. Ecclesiastical affairs drifted into the background and fishing communities became his focus and his life.

The likes of Neil and Daisy Gunn, Compton McKenzie and Eric Linklater became firm friends.

Indeed both Neil and Sir Compton were to contribute forewords to his books. Compton had reviewed Peter’s writing for the Daily Mail commenting that:

“Mr Ansons books are prized possessions on my bookshelves.”

It has even been suggested that Neil’s Silver Darlings might not have reached publication if Peter had not encouraged the man to publish and be damned.

Peter wrote at the time that:

“In Scotland … so far as I could discover I was the only Papist earning a living by literary and artistic work in the vast diocese of Aberdeen.”

Soon after moving into Macduff ‘s Harbour Head the local parish priest designated Peter’s house as an Apostleship of the Sea ‘Service Centre’. As a consequence a constant stream of mariners of all faiths and nationalities found their way to his door and in wartime, service folk on leave from the armed forces frequented his open house.

He had begun the Apostleship many years before with the vision of creating a worldwide organisation. At Harbour Head, Peter soon adopted the view that perhaps men rather than administrative machinery were required; Apostles were more needed than an Apostolate.

During this period he wrote and sketched at a furious pace adopting the practice of making at least one drawing before breakfast. He had spent six months in an earth floored fisherman’s cottage in Portsoy prior to moving to Harbour Head during which time he completed The Catholic Church in Modern Scotland. During his years in Macduff his writing included classics such as A Roving Recluse, Life on Low Shore and the best-selling classic British Sea Fishermen.

At the behest of the Scottish Nationalist Party and with a foreword by writer Neil Gunn he penned a vitriolic political pamphlet ‘The Sea Fisheries of Scotland are they Doomed’ which examined in some detail the causes for the decline in the fortunes of the inshore fishing industry in the 1930’s.

Books as diverse in nature as How to Draw Ships and the 1956 Official Guide to Banff followed and are part of his legacy alongside possibly his final work Building Up the Waste Places in which he explores the life and work of Aelred Caryle and Fr. Hopkins, each of whom played key roles in the restoration of Benedictine Monastic life in the post Reformation church.

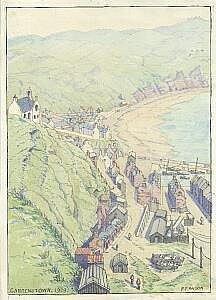

A founder member of the Royal Society of Marine Artists Anson published over 40 books, and contributed to many more. His artistic output numbers literally thousands of drawings and watercolours and many of his books are prolifically illustrated with harbour scenes and pier head paintings.

A founder member of the Royal Society of Marine Artists Anson published over 40 books, and contributed to many more. His artistic output numbers literally thousands of drawings and watercolours and many of his books are prolifically illustrated with harbour scenes and pier head paintings.

In 1958 Peter left Macduff and moved to a cottage near Ramsgate Abbey. A further brief stay in Portsoy followed in 1960 and in 1961 he moved to Montrose.

Made a Knight of the Order of St Gregory by Pope Paul VI in 1966 in recognition of his scholarly work he became, in 1967, the first Curator of the Scottish Fisheries Museum at Anstruther.

His later years were spent back at Caldey Island and finally at Sancta Maria Abbey in East Lothian.

He died in St. Raphael’s Hospital in Edinburgh in July 1975 and is buried in the private cemetery at Nunraw Abbey.

Aspects of Peter’s life remain unclear and some personal diaries and correspondence remain unavailable to historians until 2040. He was seemingly barred from attending a friend’s funeral at Doune Kirkyard in Macduff, shuddered at the loss, but in time recovered and moved on.

Moray Council Museum Service hold a substantial collection of Peter Anson’s work some of which is on public display at the Falconer Museum in Forres. They also hold an archive of his letters and diaries plus his personal library. Buckie Fishing Heritage Centre and Buckie Library also hold Anson paintings.

Courtesy of Stanley Bruce, Macduff sports a sculpture in memory of Peter but perhaps the most fitting tribute to his life are in the words of an anonymous Buckie fisherman quoted on the flyleaf of the 1930 edition of the best selling classic: ‘Fishing Boats and Fisher Folk on the East Coast of Scotland’.

“Peter’s the maist winnerfu’ mannie ah ever met, well kent in scores o’ ports, a man wi’ the sea in’s bleed, a skeely drawer o’ boats an’ haibers an’ fisher fowk, a vreeter o’ buiks, a capital sailor, an’ a chiel … He’s a byordinar mannie.”

© Duncan Harley

With thanks to the Moray Museum Service, the Andrew Paterson Scottish Highland Photo Archive and Aberdeenshire Library Service. First published in the November 2015 edition of Leopard Magazine

- Comments enabled – see comments box below. Note, all comments will be moderated.