To coincide with the installation and unveiling of The Robert The Bruce statue in Aberdeen, Voice’s Alex Mitchell presents a three part account of King Robert’s life, his impact on historical events, and the role of powerful rival family the Comyns.

Scotland in the 13th and 14th centuries was an intensely feudal and conservative kingdom.

When Robert Bruce, born 1274 in Ayrshire, made his bid for kingship in 1306, he was supported by a few earls, a fair number of barons and a considerable following of lairds and the lesser gentry.

On his father’s death in 1304, Bruce at the age of thirty was Earl of Carrick, lord of Annandale, …lord of a great estate in Huntingdonshire in England.

He owned a house in London and was lord of the suburban Manor of Tottenham; he was, in fact, the richest man in England. In the north of Scotland he held part of the Garioch and was the keeper of the fortress of Kildrummy and of at least three royal forests – Kintore, Darnaway and Longmorn.

The Scottish nobility was rent asunder by feuds and factions, in an age of horrors, brutality, intrigue and squalor. For Bruce’s bid for power to succeed, he had to achieve either the support or the elimination of John Comyn, Earl of Badenoch.

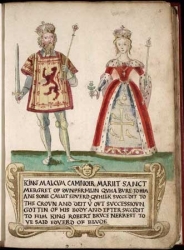

Like the Bruces, the Comyns were of Norman-French, i.e., Viking, origin. After the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, many of the Norman-French nobility were granted lands in Scotland by King Malcolm (Canmore) III. In 1212, William Comyn married Marjorie, the only child of Fergus, the mormaer or earl of Buchan.

There were now three branches of the Comyn family: the Kilbride Comyns, the Badenoch Comyns and the Buchan Comyns. They were tied together by blood and marriage, and their territories extended all the way across Scotland from the Aberdeenshire coast westwards through Badenoch and Lochaber to Loch Linnhe.

Of the thirteen earldoms in Scotland, the Comyns controlled three.

In 1242, Alexander Comyn was Earl of Buchan, Walter Comyn was Earl of Menteith and John Comyn was Earl of Angus; all as the result of (further) marriages to Celtic dynastic heiresses, with the result that the Comyns had come to have as much Celtic as Norman blood, or genes.

They had also a high degree of influence over the earldoms of Ross, Mar and Atholl. The acknowledged Chief of the Comyns was the feudal Lord of Badenoch and Lochaber. Upwards of sixty belted knights were bound to follow his banner with all their vassals, and he made treaties with princes as a prince himself. The Comyns were the most powerful extended family in Scotland throughout the 13th century, but the tragic events of 18 March 1286 marked the beginning of their end.

After an evening of drinking and carousing, King Alexander III, born 1241 and therefore aged 45, decided to make the difficult journey from Edinburgh Castle to the then residence, on the other side of the Firth of Forth, of his young French wife, Yolande. It was a dark and stormy night. Others tried to persuade him to wait until morning. He refused. His horse lost its footing and the King fell down a cliff to his death. This was an absolute and unmitigated disaster for Scotland.

Alexander had been an effective and well-regarded king, as was his father, Alexander II. Their combined reigns, from 1214-86, are regarded as the “Golden Age” of medieval Scotland. Alexander III had been crowned King of Scotland at the age of eight, and was married to Princess Margaret, daughter of King Henry III of England in 1251, when he was ten. But Margaret and all their children pre-deceased him, and Alexander had no living brother, nephew or cousin. His only direct heir was his grand-daughter, Princess Margaret, the Maid of Norway.

King Edward I of England was the Maid’s great-uncle. Soon after she was born, Alexander III and Edward, who were friends as well as brothers-in-law, discussed the possibility of a royal marriage between little Margaret and Edward’s young son, the future Edward II. This would have meant an effective Union of the Crowns of England and Scotland. It was widely felt in Scotland that such a marriage would be preferable to the problems a marriage to any of the Scottish nobility would inevitably create.

King Edward’s troops proceeded to occupy nearly all the major Scottish strongholds, including the Castle of Aberdeen.

In 1290, the eight-year old Margaret was brought by ship from Norway for Scotland; but she became violently sea-sick during the voyage, and died shortly after landing. Scotland now had no clear heir to the throne. The intended Union of the Crowns had to wait, in the event, for over three centuries, until the death of Queen Elizabeth of England in 1603.

King Edward took full advantage of the confused situation. By a combination of promises and threats he became accepted as the Lord Paramount, or Overlord, of the Scottish Kingdom, and was invited to adjudicate in the competition for the Succession. There were thirteen “Competitors” for the Throne of Scotland. King Edward’s troops proceeded to occupy nearly all the major Scottish strongholds, including the Castle of Aberdeen.

Three principal “Competitors” for the throne emerged; John Balliol, Robert Bruce and John “the Black” Comyn, the Earl of Badenoch This last threw his support behind John Balliol, mainly because Balliol was his brother-in-law, but Balliol did have a slightly stronger claim, in terms of descent from King David I, than did Bruce. King Edward favoured Balliol, whom he regarded as weaker and more compliant than Bruce. John Balliol was duly crowned on 17 Nov 1292 and swore fealty to Edward at the latter’s insistence. Balliol rewarded the Comyns with additional lands and titles, and John Comyn became his chief advisor. The Bruces refused to acknowledge or serve the new King.

King Edward had a high degree of influence in Scotland. King John paid homage to Edward, in recognition that Edward was his Overlord. In fact, most of the Scottish nobility had land and interests in England, and therefore had feudal obligations towards the kings of both Scotland and England. This created a potential conflict of interest, especially in the event of any dispute or armed conflict between Scotland and England.

King Edward sought to improve relations with the Comyns. In 1292, he gave John Comyn of Buchan the forests of Durris, Cowie and the Stocket forest at Aberdeen. He also gave permission for the marriage of his cousin’s daughter, Joan de Vallance, to John Comyn of Badenoch.

John Balliol has come to be seen as a weak king, although his perceived weakness was exacerbated by the extraordinary ruthlessness and aggression of King Edward, whose behaviour is difficult to explain in rational terms.

The Bruces had withdrawn from public affairs. They chose not to take part in the defence of Scotland, but instead paid homage to King Edward

It was obviously in the best interests of England to retain and support the relatively compliant John Balliol on the Scottish throne, but instead, Edward set out to destroy him. Balliol retaliated by negotiating a defensive agreement with France – the beginning of the Auld Alliance. In revenge, Edward besieged Berwick – then the largest Scottish town and principal seaport – and massacred all its inhabitants, including women and children.

The Scottish army was defeated at Dunbar in 1296 and the castles of Roxburgh, Edinburgh and Stirling surrendered to the English.

The Comyns were amongst those of the nobility who fought against King Edward. The Bruces had withdrawn from public affairs. They chose not to take part in the defence of Scotland, but instead paid homage to King Edward. They lived mostly in England, and retained possession of their English estates. The Balliols and the Comyns fought hard for the independence of Scotland, and they suffered for it in terms of both lands and freedom.

In anger at Bruce’s inaction, King John (Balliol) confiscated his estate at Annandale and granted it to John Comyn, Earl of Buchan. The Bruces never forgave this insult.

King John (Balliol) submitted to his English overlord at Stracathro on 7 July 1296, abdicated his throne and was taken prisoner with his family to the Tower of London. King Edward embarked on a triumphal progress through Scotland; he spent five days in the Castle of Aberdeen in mid-July, 1296. He returned to England in October, leaving Scotland under an English military administration, a harsh form of direct rule.

This led to a major revolt in 1297, involving both the Comyns and the Bruces, but under the joint leadership of William Wallace in the south and Andrew de Moray in the north. They scored a major victory against a much larger English army at the Battle of Stirling Bridge on 10 September 1297.

In March 1298, Wallace was made Guardian Of The Realm in the name of the deposed King John Balliol, and was knighted; but Wallace never sought to be King himself. Andrew de Moray, possibly the real military genius of the two, had been mortally wounded at Stirling Bridge, and died shortly afterwards.

William Wallace, the younger son of a minor landowner in Ayrshire and not, therefore, a member of the Anglo-Norman or Scoto-Norman aristocracy, seems to have been motivated by a combination of genuine patriotism and intense hatred of the English and of anyone he identified as their allies. He led a large and unruly army into Northumberland and Cumbria, which behaved with extraordinary savagery, even by the standards of the time. The English were killed wherever they were found – old men, women and children. King Edward was bound to retaliate.

Dont miss part 2 of this account in Aberdeen Voice next week.