By Alex Mitchell.

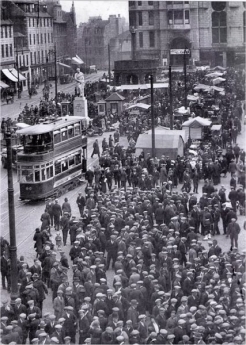

In 2007 Aberdeen City Council decided to relocate the International Market to Union Terrace during its visit of 10-12th August. Prior to this, the Market has generally been placed in the Castlegate on Fridays and in the mid-section of Union Street on Saturdays and Sundays.

The relocation to Union Terrace was prompted by Police concerns about serious traffic management problems arising from the blocking-off of Union Street.

We had consistently argued that the Market should occupy the Castlegate throughout its 3-day visits. The Castlegate is Aberdeen’s historic market place; it had adjacent parking in the Timmer Market and East North Street car parks; it needed the visitors and their custom and it involved no disruption to traffic and bus-routes at all. Beyond all this, the Market had, at least on Fridays, given us a reason and incentive to visit the historic Castlegate, which affords the most spectacular views of Aberdeen’s best buildings and the mile-length of Union Street – views which can be seen from the Castlegate and nowhere else.

However: in the Press & Journal of 31 July ’07, Mr Tom Moore, ACC’s City Centre Manager, was quoted as follows: “None of the events at the Castlegate has been an absolute success … we’ve tried everything to encourage people to come, but they just won’t … some of the stalls do quite well, but others are just dead”.

This correspondent would have to admit, from personal observation, that neither the International Market on Fridays nor the German Market held in the Castlegate during the weeks preceding Christmas ’06 ever seemed to be doing much business; there was little of the buzz and vibrancy of the Market when located on Union Street, on Saturdays and Sundays. Part of the reason is that the Castlegate is perishing cold much of the year, because of the wind-chill factor blowing up Marischal Street from the Harbour. Even the stallholders, who were used to standing about in the cold, could not take it.

All this has serious implications as regards plans to regenerate the Castlegate.

The International Market is a genuinely popular event. If not even the Market can attract people into the Castlegate, then it is difficult to see what can or will.

To the extent that ‘regeneration’ is about planting the seeds of enterprise, investment and employment, the Castlegate seems almost like blighted or toxic land in which nothing thrives or succeeds, as it should.

The main problems are (a) that the Castlegate is a backwater, some way removed from the main centre of activity and not an obvious route way of choice to anywhere much; and (b) that for all its historic significance, people do not find the Castlegate an attractive or congenial place. Visitors are repelled by, from recent observation, blatant and overt drug-dealing; by deathly-pale junkies collapsing in the street in front of one; and by Aberdeen’s ever-shifting population of out-of-control drunks, winos and aggressive and obstructive beggars.

In point of fact, the Castlegate has been a concentration of social ills for a long time back, certainly from the mid-19th Century. The real centre of activity in Aberdeen was always at the junction of Broadgate and Castlegate and around the Mercat Cross (of 1686, but not the first), which was originally located in front of the Tolbooth. The Mercat Cross was relocated to its present position in 1842 and for a time served as the city’s Post Office. The gentry used to have their town houses in the Castlegate, mainly on the south (harbour) side, but the advent of Union Street from 1805 encouraged the better off to move westwards of Union Bridge.

A huge military Barracks was built on the Castle Hill in 1794 and was occupied by the Gordon Highlanders until the 1930s, after which it became a form of slum housing. The Castlegate’s proximity to both the Barracks and the seaport made it a concentration of drunkenness and prostitution.

It was for this reason that the Salvation Army located their Citadel there in 1896.

The Citadel has done much good work in its time, but it has in certain obvious respects served to reinforce the Castlegate’s magnetic attraction for down-and-outs of various kinds. The drugs rehab & treatment centre under construction in the Timmer Market car park may well have similar effects and will quite possibly kill the Castlegate stone dead.

A neighbourhood or locality, or indeed a town or city, has to be much more than just a cluster or agglomeration of buildings and streets. There has to be a base of economic activity, of business, trade and employment, otherwise it becomes merely a ghost town or, at best a heritage museum like Venice or, prospectively New Orleans. One might think also of the great medieval Flemish seaport of Bruges, through which all Scotland’s exports to Europe were channelled, until its river Zwin silted up around 1500, and the trade shifted over to Antwerp. Bruges remained trapped in a 15th Century time warp for the next 500 years, nicknamed Bruges-la-Morte.

few of us ever go there now; it has become another of Aberdeen’s shunned places

After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, President Bush promised to rebuild New Orleans, presumably in the belief that city equals buildings, but the economic base of New Orleans faded away long ago, not least because of corrupt and incompetent civic administration, poor public services and rampant criminality.

Once legitimate business activity withdraws, everything else goes too, including the economically active part of the population – most of us have to live where we can earn a living. There are obvious lessons here as regards Aberdeen’s city centre. Policy needs to be more consciously directed towards economic regeneration, to creating a more favourable and attractive environment for business enterprise and investment, job-creation, the local resident population, visitors and shoppers, before it is all too late. Unfortunately our local power elite seems to have completely the wrong idea as to what this involves and requires.

On Tartan Day, your correspondent decided to go for a wander around Castlehill, mainly with a view to taking some photographs of the remnant of the wall that surrounded the Georgian military Barracks, which were demolished in the 1960s and replaced by the present tower blocks of council flats, Marischal Court and Virginia Court.

Castlehill is an immensely historic part of Aberdeen and affords spectacular views across the harbour and beach area, but few of us ever go there now; it has become another of Aberdeen’s shunned places. Castlehill is dominated by the giant tower blocks to the extent that non-residents feel we have no business being there, and are effectively excluded.

A great many people must live in the tower blocks, but on a bright, sunny Saturday afternoon, and with Tartan-related activities going on nearby in the Castlegate, there was hardly another soul to be seen anywhere on Castlehill. The effect is isolating and intimidating. A vicious circle is engendered, whereby mainstream citizens stay away, the locality is increasingly monopolised by anti-social elements and becomes even more of a no-go area, and so on.

It has been a real achievement, in a negative kind of way, to transform so many hitherto vibrant parts of Aberdeen into dead zones, apparently devoid of population or legitimate business activity and employment. Photographs of the Mounthooly area, taken as recently as the 1960s, show streets, granite-built tenements, shops, businesses and large numbers of people walking the streets and pavements.

thousands of Aberdonians must have worked there, but somehow it already seems to have been airbrushed from the collective memory

As with Castlehill, there are still lots of people living in the Mounthooly area, in huge tower blocks such as Seamount Court and Porthill Court, but there are hardly any local shops and businesses such as might provide local people with employment or a reason to go out and about.

In consequence, even on a bright, sunny weekday afternoon, there is hardly anyone to be seen anywhere.

The name ‘Porthill Court’ is the one official acknowledgement that the Port Hill, opposite Aberdeen College on the Gallowgate, was and remains the highest of the seven hills on or around which Aberdeen stands, so-named after the Gallowgate Port, which guarded the northern entrance to the Burgh. The huge Porthill Factory (linen, textiles) stood on this site for about 200 years, from about 1750 until its demolition in 1960, and thousands of Aberdonians must have worked there, but somehow it already seems to have been airbrushed from the collective memory.

Similarly Ogston & Tennant’s soap and candle factory; the former front office remains at No. 111 Gallowgate. These were local firms, employing local people, most of whom would have walked to work, going in past their local shops for their morning paper, fags and rowies on the way.

There is no point in romanticising what must have been fairly bleak and grim workplaces; but it must have been easier then for a young person to find their way into paid employment when the workplaces were just up the road, when you already knew people – friends, relations and neighbours – who worked there, equally when you and yours were weel-kent locally, than can be the case nowadays if you live halfway up a tower block in Castlehill or Mounthooly and the only jobs available are with firms nobody has ever heard of, located on industrial estates miles away in Altens or Westhill.

Contributed by Alex Mitchell.