By George Anderson.

I was shopping in Turriff last week, failing, as usual, to find a low-salt, low-fat, cholesterol-free, high-fibre titbit for my supper. Something healthy enough to turn my doctor’s frown to a smile, but with a hint of indulgence. Something with the life enhancing promise of muesli and the bohemian decadence of a Walnut Whip.

In pursuit of this unlikely product, I circled the supermarket’s food hall until I was light-headed.

I eventually concluded that I could have decadence or health, but not both in the same foodstuff and finally fell to considering a carton of peely-wally looking cottage cheese with a kirn of minced greenery through it.

A note on the side claimed that the carton contained eighty-five percent of the vitamins and minerals needed to survive the day, including folic acid, riboflavin and iron. I was just swithering whether to look for something nearer ninety percent – just to be on the safe side – when I realised I was obsessed with nutrition. “When did this start”, I wondered? Having been an Aberdeen loon in the sixties when the government urged us to eat butter, milk and cheese as if the four minute warning had just sounded, I certainly wasn’t so fussy about what went over my thrapple.

I stuffed my face each morning with a brace of Aberdeen rolls. By the time I entered the Grammar School in 1966 I’d eaten eight times my body weight in dough – and remember, I’m not talking about dough with cholesterol-lowering plant extracts, Omega-3, or bifidus digestivum. I’m talking about dough with saturated fat and enough salt to corrode the tailpipe of a Morris Minor.

lard was so popular that people would spread it on bread if they had to, but get it they must.

Nutritionally speaking, things didn’t improve much at lunchtime. The fear of being force-fed semolina kept me permanently away from school dinners and I largely survived on a diet of Sports Mixtures and sherbet-filled flying saucers.

Supper consisted of polony which Ma bought by the yard from the Home & Colonial in George Street. Cut into slices, polony could be grilled, fried, or used to wedge open doors during flittings. For sheer versatility and taste, no other sausage came close.

When Ma was unable due to weemin’s trouble to make supper, the spurtle of power passed to Da. Da’s generation embraced the concept of ‘Can’t Cook, Won’t Cook’ long before Ainsley Harriott ever shoogled a skillet in earnest. In those days working class men believed that standing too close to a domestic appliance (close enough to use it) shrivelled the gonads, so Da avoided cooking whenever possible. This often meant pottit heid: scrapings of meat from a cow’s skull, suspended in meat jelly. It was cheap and required no cooking. I wish it had required no eating either but I had no choice. I wanted to start a helpline for those exposed to pottit heid but Da said “No”.

Supper was followed by mugs of tea, neep jam (What else could it be? It wasn’t made from any fruit I’ve ever tasted) and white panned loaf from which all nutrients had been diligently thrashed. Variety was added to our diet by means of the chipper supper. Did this increase our life expectancy? It’s unlikely. These were the days when lard was so popular that people would spread it on bread if they had to, but get it they must.

Our nearest chipper was Archie’s in John Street. The ten o’clock shout of “Last orders” in Cooper’s Bar across the street from Archie’s heralded a nightly stampede for all things deep fried that made the customer’s side of Archie’s counter look like the floor of the Tokyo stock exchange. If elbowing your way through this stramash for a single mock chop wasn’t worth the inevitable black eye, you could stick your nose in the air and follow the whiff of over-used fat all the way to the White Rose chipper in Mounthooly. Here you could buy a tanner special: a shovel of chips and a fragment of deep fried sea-life that might be coalfish, starfish or seahorse depending on the by-catch landed at the fish market that morning.

“Fit kind o’ fish is this, mister?”

“Fit kind wi’d ye like it tae be, loon?”

“Huddock?”

‘It’s huddock then. Now, dee ye wint salt an’ vinegar or no?’

There were times when I tried to improve my diet by making stuff for myself. Like the day I was foolish enough to rustle up a batch of black sugar ale from a recipe my grunny gave me. Black sugar ale: The very phrase was as romantic as a Barbara Cartland novel. It sounded like something Long John Silver might have drunk. If he did he was a gype. Only a qualified chemist could supply the main ingredient: a bullet of liquorice so concentrated I had to sign a book before the pharmacist would hand it over.

When I got home I removed the slug of liquorice from the bag using the coal tongs, dropped it into a Hay’s Dazzle bottle filled with water and hastily screwed the top back on. The concoction was to be left undisturbed in a dark place for at least six weeks, so I stuck it on a shelf in the coal cellar. I reclaimed the cobwebbed bottle two months later by which time the contents had transformed themselves into an anthracite coloured sludge of extraordinary laxative power. I opened the bottle and took an exploratory whiff of the fumes lurking in the neck of the bottle and ……..well, let’s just say they were sliding polony under the lavvy door for days.

Why didn’t we all come down with scurvy and double rickets? Probably because every Saturday Ma bought a tea-chest of ‘chippit fruit’ from The Orchard in Upperkirkgate. Chippit fruit. Nowadays I suppose it would be called ‘distressed’ fruit — was a generic term for all the fruit the fruiterer couldn’t palm off on anybody sober: oranges that had been knelt on, terminally bruised bananas or melons the shop assistant had been playing keepie-up with during the week. This weekly super-boosting of our immune systems most likely kept us all out of hospital.

I returned to the present to find myself still clutching the cottage cheese. I intended to head straight for the checkout with it but an unseen hand guided my trolley to the cold meats section of the store, where I stood gazing at a yard of pre-packed polony with a nostalgic eye. Maybe, just maybe, polony was as packed with vitamins and minerals as my reluctantly chosen cottage cheese. I examined the food label to see.

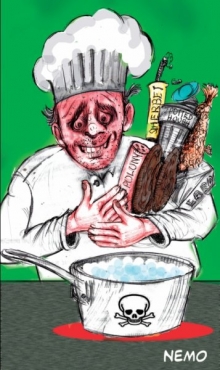

The main ingredients were listed as pork and bacon. Then came the phrase: ‘Other Meats’. Which other meats I thought? Badger? Three‑banded armadillo? Rusk followed that. Rusk is a variety of edible sawdust the government allows butchers to mix with meat while the customer roots distractedly in the veggie basket for a decent neep. Further down the list where the tiniest of writing strained my prescription glasses to their limit, I found E450K (Wasn’t this the stuff they put in wallpaper paste to kill fungus?); Colour 128 (I Googled it when I got home. It’s in the Dulux range as Fencepost); and anti‑oxidant 301 (an early rocket fuel used by Wernher von Braun if I wasn’t mistaken). No mention of folic acid, riboflavin or iron.

I stood there for some time looking from cottage cheese to polony and back again. I know our sixties diet would be enough to make today’s nutritional boffins at the Rowett Institute cowk on their Special K, but don’t they say that a little of what you fancy does you good? It just depends on your definition of ‘little’ I suppose.

“Dee ye ken the polony sassidge is buy-een-get-een-for-nithing jist noo?” the lassie at the checkout asked,

“Dee ye wint tae rin back and get anither een?” I took the lassie up on her offer, put the cottage cheese back where I found it and set off home.

Over the next few days I managed to eat the whole two yards. Guilt free. Or so I thought. The night I scoffed the last of it I fell asleep with a contented smile but looking like I’d swallowed a fully inflated beach ball. At two in the morning, I sprang bolt upright out of a nightmare, peching like a ploughman’s horse at lowsin’-time. I was back in the Aberdeen tenement where I grew up. A gang of vitamins had infiltrated our house through a crack in the pointing. Armed with a tattie-masher, Ma pursued the intruders from room to room, clambering over furniture and twice falling down the back of the radiogram before driving them out.

Before I fell sleep again I promised myself that in the morning I’d devote my life to Ryvita and green tea. I should be fine so long as I stay well away from the cold meats section of the supermarket in Turriff.