By Alex Mitchell.

A bright, sunny Thursday afternoon. Left the car at Union Square and walked through the main aisle. A fair number of mostly young people are walking briskly and purposefully to and fro rather than window-shopping or going into any of the shops, other than Apple. Out on to Guild Street. The Edwardian frontage of the Station Hotel (1901) looks well in the bright sun.

Across Guild Street and into the recently-designated ‘Merchant Quarter’ around the Green. This whole area, as around the triangular site of the Carmelite Hotel – Trinity Street, Carmelite Street & Lane, Stirling Street and Exchange Street – is characterised by narrow streets, alleys and wynds, small medieval plots and very tall buildings which shut out the sunlight. The overall effect is dark, congested and Gothic, a bit like the medieval Paris depicted in Dieterle’s film of The Hunchback Of Notre Dame (1939).

There is also a marked absence of green space or trees. As part of The Green Townscape Heritage Initiative, ACC has laid down concrete rectangular enclosures for shrubs and trees, as in Carmelite Street and Rennie’s Wynd, but these will take time to establish themselves. The Green itself is in deep shade at 1.30 pm, with nobody much going about.

Out by Hadden Street, on to Market Street and along Trinity Lane to Shiprow. The huge City Wharf development, originally scheduled for completion in December 2009, was left unfinished when the Edinburgh-based developer, Kenmore, folded. The development is now owned by SI City Wharf Ltd, and what is striking is the lack of any apparent urgency to finish the job. Even the Ibis Hotel, which was relatively well advanced, remains as yet unfinished. The Harbour is full of oil vessels. Oil-related activity has surged now that the world price has reached $100 per barrel, comparing favourably with long-run extraction costs estimated at $30-50 per barrel.

Across Union Street and into Broad Street. Marischal College, newly restored, shines brightly in the sunshine, the single most iconic building in Aberdeen.

It is a pity the same treatment cannot be applied to the adjacent and contiguous Greyfriars Kirk.

The Church of Scotland wants £1.25 million for Greyfriars Kirk; but Aberdeen City Council estimate its value as being in the vicinity of zero, given that nobody else wants it and the building is full of dry rot.

Down Queen Street, once an elegant Georgian residential thoroughfare inhabited from 1791 by the young George Gordon Byron, later Lord Byron, and his temperamental mother, Catherine Gordon, heiress to Gight Castle. They later moved to Broad Street and young George attended the Grammar School, then at its original site on Schoolhill. Now Queen Street and Broad Street have no resident population at all.

Round by Aberdeen Arts Centre, in John Smith’s South Church of 1829 at the crossroads of King Street and North Street. Along East North Street towards the Castlehill roundabout. The new low-rent flats built around the old Timmer Market car park have been finished for some reason in a drab brown/black slate-like material. By contrast, the 1960s tower-block flats on Castlehill, viewed at a distance and in the full glare of the afternoon sun, achieve something like elegance and symmetry.

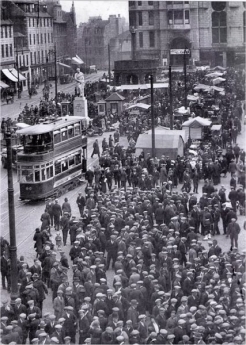

In by Justice Street to the Castlegate which is barely ticking over. Fifty-odd years ago, this was the city’s main bus/tram interchange. Alex ‘Cocky’ Hunter’s emporium and the Castlegate market were in full swing and the Sick Kids’ Hospital was round in Castle Terrace.

Up on to Castlehill itself by the one-time Futty Wynd. There remain long stretches of substantial granite wall from the C.18th Barracks and the earlier Cromwellian fortifications of the 1650s, and a circular indentation, as of a gun emplacement, overlooking the harbour. The Gordon Highlanders left the Barracks in the 1930s and these impressive Georgian buildings became a form of emergency housing until their demolition in the 1960s. There must still be people around now, between fifty and eighty years of age, who were brought up in that distinctly bleak and austere environment.

The odd thing now is that there must be hundreds of people living in the present blocks of flats, Marischal Court and Virginia Court – the equivalent of a large village – but at 2.30 on a sunny weekday afternoon there is nobody going about on Castlehill apart from a couple of Council workmen. Kids would still be at school at this time of day, but even so the entire vicinity is unnervingly silent and still and full of ghosts.

Down Marischal Street and along Regent Quay. The waters of the old natural harbour reached the foot of the Castle Hill at high tide, a line roughly corresponding to Virginia Street. The area between Virginia Street and the present harbour-front is the old Shorelands, a muddy inter-tidal zone once inhabited mainly by crabs, but reclaimed from the mid-C.18th and since occupied by Commerce Street, Mearns Street, James Street, Water Lane and the lower end of Marischal Street.

The view up Mearns Street is dominated by the shining tower of the Castlehill flats. Virginia Street used to be a narrow and meandering cobbled thoroughfare, but is nowadays yet another urban motorway, wider than it really needs to be and at the expense of much of the old toun. It is an unpleasant experience to walk the narrow footpath as between the Shore Porters’ building and the monster trucks charging straight into the permanent traffic gridlock of Guild Street and Market Street. Back along Shore Lane, across the foot of Marischal Street and past Theatre Lane – an almost subterranean link to Virginia Street and well worth exploring. But not today.

Contributed by Alex Mitchell.