‘I want to be there, there being no top of tree, no glory or honour, simply working good and well, and producing stuff that will last the ages.’ (William Lamb, 1923)

As a young lad growing up in Montrose in the 1960s I first came across William Lamb’s work when my uncle used his old studio. Surrounded by statues of massive figures, disembodied heads and nude young boys, the place had a strange, neglected atmosphere. These days, his large bronze figures are proudly displayed in the town and the studio is open to the public. John Stansfeld’s new biography can only add to the reputation of an important artist, often described as ‘a Scottish Rodin’. Graham Stephen reviews.

Lavishly illustrated, the book details Lamb’s artistic achievements and gives us insight to a complex man who, despite a reluctance to leave his beloved home town, once solo-cycled over 4000km through Europe on his trusty Raleigh, had a trial for Aberdeen FC and briefly became a playmate of the current queen.

Lavishly illustrated, the book details Lamb’s artistic achievements and gives us insight to a complex man who, despite a reluctance to leave his beloved home town, once solo-cycled over 4000km through Europe on his trusty Raleigh, had a trial for Aberdeen FC and briefly became a playmate of the current queen.

From a variety of sources, most notably the Simms’ family archive, Stansfeld examines Lamb’s struggle to create superb work despite personal hardships.

Rooted in his community and landscape, Lamb chose to ‘starve among (his) own folk’ rather than dilute his native culture by moving away in search of a more lucrative market.

His portrayal of working men and women, real people often struggling with life and the elements, are a particular feature of his work.

The Lamb who enlisted in 1915 was a skilled stonemason, respected artist and all-round sportsman. He returned a broken man, temporarily struck dumb, physically and psychologically devastated and, tragically, with a permanently damaged right hand.

By sheer force of will he taught himself to work again with his left, skilled enough to win commissions to create the war memorials which funded his European travels in 1923. His surviving letters from this trip are one of the highlights of the book, an insight into a man with a meticulous eye for detail, realising that art would be his life, never taking the easy path.

Stansfeld’s detailed research unearths intriguing aspects of Lamb’s life. He was almost perpetually penniless, relying on friends to feed him, often on a daily basis. Any money he made was invariably used to fund materials, or help fellow artists like Ed Baird, another undervalued Montrose talent.

The local council, disturbed by his nude figures, suggested adding kilts for a major exhibition, and Lamb reacted predictably. He was a lifelong teetotaller, disgusted by his alcoholic father, supressing his probable homosexuality, living alone in a freezing attic. His attendance at fledgling Nationalist meetings held by poet Hugh MacDiarmid in the 1920s was more likely for the heat of the fire than for the rhetoric.

Lamb later took his revenge on the arrogant MacDiarmid by making his bust look ‘like him’.

Most intriguing is his commission to sculpt Princess Elizabeth in 1932 when he spends many hours alone with the future queen, playing house and crafting plasticine tea-sets, before returning to Montrose, and his ultimate decline.

In a rare speech in 1930 William Lamb described Scottish sculpture as ‘hopeless’, unappreciated and unloved by the majority of the population. Even today it would be hard to argue against him. This fine book should help to bring his achievements to a wider audience.

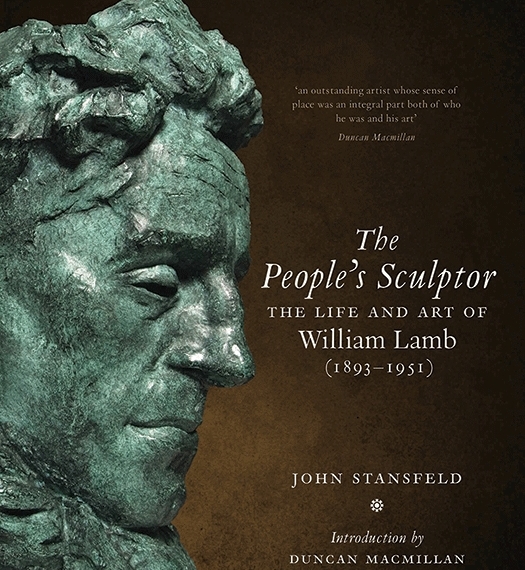

The People’s Sculptor: The Life and Art of William Lamb (1893-1951)

John Stansfeld

Birlinn Ltd

£14.99

- Comments enabled – see comments box below. Note, all comments will be moderated.

One Response to “Montrose Sculptor’s Biography Reviewed”