Dave Watt presents the third article of a series of three concerning ‘strops and arguments’ in the olympics.

“May joy and good fellowship reign, and in this manner, may the Olympic Torch pursue its way through ages, increasing friendly understanding among nations, for the good of a humanity always more enthusiastic, more courageous and more pure.”

– Baron Pierre de Coubertin – founder of the modern Olympics. Athens 1896.

1948 Olympiad London.

Although World War II was over, Europe was still ravaged from the war. When it was announced that the Olympic Games would be resumed, many debated whether it was wise to have a festival when many European countries were in ruins and people were near starvation.

To limit Britain’s responsibility to feed the participants, it was agreed that they would bring their own food. No new facilities were built for these Games, but Wembley Stadium had survived the war and proved adequate.

No Olympic Village was erected; the male athletes were housed at an army camp in Uxbridge and the women housed at Southlands College in dormitories. Germany and Japan, needless to say, were not invited to participate.

It was a generally good natured Olympiad, apart from US protests after their relay team was disqualified and the second placed British team had to give up their gold medals and received silver medals – which had been given up by the Italian team. The Italian team then received the bronze medals which had been given up by the Hungarian team.

1952 Olympiad Helsinki.

A total of 69 nations participated in these Games, up from 59 in the 1948 Games. Japan and Germany were both reinstated, but getting back to normal, the strops began with only West Germany providing athletes, since East Germany refused to participate in a joint German team.

The Republic of China, listed as “China (Formosa)”, withdrew from the Games on July 20, in protest at the People’s Republic of China’s men and women being permitted to compete. Israel entered for first time.

The US won 40 golds and a total of 76 medals with the new participants the USSR coming second with 22 golds and a total of 71 medals which just goes to show what you can do if sport is open to the entire population instead of being the preserve of a few toffs.

1956 Olympiad Melbourne.

In Europe, the USSR, suspecting the resurgence of fascism in Hungary, invaded the country, while the British and French attacked Egypt in order to regain control of the newly nationalised Suez Canal.

As a sign of protest 6 countries withdrew from the Olympics. The Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland withdrew because of the events in Hungary, while Iraq and Lebanon withdrew because of the conflict in Suez.

Less than two weeks before the opening ceremony, the People’s Republic of China also pulled out because the Republic of China (Taiwan) had been allowed to compete. Although the Games were not cancelled, there were many episodes such as the water-polo match between Russia and Hungary which turned into a major aquatic ruck.

On the plus side, East and West Germany were represented by one combined unified team.

Strangely, as the quarantine laws did not allow the entry of foreign horses into Australia, equestrian events were held in Stockholm in June 1956. The rest of the Games started in late November, when it was summertime in the Southern Hemisphere.

The Butterfly event in swimming was “invented” for the 1956 Games after some swimmers had begun to exploit a loophole in the breaststroke rules and rocketed past their more traditional opponents.

The Soviets dominated the Olympiad, winning 98 medals with 37 gold , while the Americans won 74 medals with 32 gold.

1960 Olympiad in Rome.

This proved to have a disappointing lack of strops apart from the ludicrous spectacle of Formosa representing all of China yet again. The points of interest were Abebe Bikila of Ethiopia winning the marathon bare-footed, to become the first black African Olympic champion; and a relatively unknown US boxer called Cassius Clay winning the boxing light-heavyweight gold medal.

Soviet gymnasts won 15 of 16 possible medals in women’s gymnastics, and the USSR won 43 golds, 29 silver and 31 bronze medals, comfortably topping the medal table.

1964 Olympiad in Tokyo.

In 1964, the IOC banned South Africa from the Games over its policy on racial segregation. The Sharpeville Massacre two years previously had been too much even for the UK and the US, who had been cheerleading happily for the South African state up until this point. The ban continued right up until 1992, following the abolition of apartheid in South Africa.

The US & Soviets shared the medals table, with the US winning more golds (36) but the USSR winning more medals overall (96 to the US’s 90).

Yoshinori Sakai, who was born in Miyoshi, Hiroshima on the day that it was destroyed by an atomic bomb, was chosen as the final torchbearer.

1968 Olympiad in Mexico City.

The 1968 Olympiad came during a turbulent year. Soviet tanks rolled into Prague, the US was fully involved in a full scale war against the Vietnamese and the country was riven internally by the repression of the Civil Rights movement culminating in the murder of Martin Luther King.

Only a few weeks prior to the games, the Mexican government had carried out a massacre of workers and students in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, known as the Tlatelolco massacre. At one point there was serious speculation as to whether the games should go ahead.

East Germany and West Germany competed as separate entities for the first time at a Summer Olympiad, Formosa became Taiwan and continued to represent mainland China – at least in the eyes of Avery Brundage, president of the IOC.

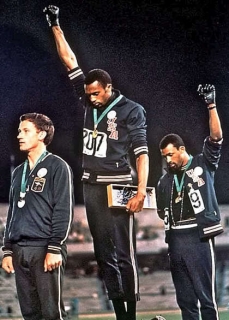

However, the creation of the most iconic symbol that was to represent the 1968 Olympiad for all time came about because of the struggle of black athletes in the US.

Amateur black athletes initially formed OPHR, the Olympic Project for Human Rights, to organise a black boycott of the 1968 Olympic Games. OPHR was deeply influenced by the black freedom struggle and their goal was nothing less than to expose how the US used black athletes to project a lie about race relations both at home and internationally.

OPHR had four central demands: restore Muhammad Ali’s heavyweight boxing title, remove Avery Brundage as head of the International Olympic Committee, hire more black coaches, and disinvite South Africa and Rhodesia from the Olympics.

Ali’s belt had been taken by boxing’s powers-that-be earlier in the year for his resistance to the Vietnam draft. By standing with Ali, OPHR was expressing its opposition to the war and opposing a campaign of harassment and intimidation orchestrated by the IOC supporters of Brundage.

The wind went out of the sails of a broader boycott for many reasons, partly because the IOC re-committed to banning apartheid countries from the Games and also because some black athletes were unwilling to sacrifice their years of training on a point of principle.

However, On October 16, 1968, black sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the gold and bronze medalists in the men’s 200-meter race, took their places on the podium for the medal ceremony wearing black socks without shoes and civil rights badges. They lowered their heads and each defiantly raised a black-gloved fist as the Star Spangled Banner was played. Both were members of the Olympic Project for Human Rights.

Supporters praised the men for their courage in making their stand.

Some people, particularly Avery Brundage, felt that a political statement had no place in the international forum of the Olympic Games. In an immediate response to their actions, Smith and Carlos were suspended from the U.S. team by Brundage, and banned from the Olympic Village.

Those who opposed the protest said that the actions disgraced all Americans. Supporters, on the other hand, praised the men for their courage in making their stand.

Peter Norman, the Australian sprinter who came second in the 200m race, and Martin Jellinghaus, a member of the German bronze medal-winning 4×400-meter relay team, also wore Olympic Project for Human Rights badges at the games to show support for the suspended American sprinters.

Norman’s actions resulted in a reprimand, his absence from the following Olympic Games in Munich, despite easily making the qualifying time, and a failure of his national association to invite him to join other Australian medallists at the opening ceremony for the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney. Rather more creditably, Tommie Smith and John Carlos acted as pallbearers at Peter Norman’s funeral in 2006.