“Savings could be made if the council withdrew music services and sold off musical instruments.”

By Ahayma Dootz.

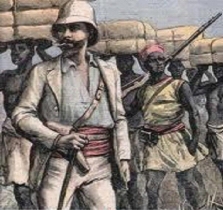

Occasional glimpses of the sun through the leafy canopy above suggested that it was not yet midday when our progress came to an abrupt halt .For some time, stumps of vine-strangled masonry had flanked our hard-won passage through the dense undergrowth and ahead of me now I saw the porters clustered around a particularly large example, their burdens abandoned.

As I approached, they parted to let me pass and I observed that this memorial had been kept free from the surrounding vegetation and that an offering of brightly-coloured flowers lay upon it.

“What d’you make of it?” I asked D’oad who was inspecting a badly-eroded inscription, “And who on earth has been caring for an ancient gravestone in this inhospitable place?”

“Inhospitable, mebbe, but no’ uninhabitit, clairly.” He replied. “An’ tak a scance at this.” He added, pointing to a faint carving lower down.

“Good grief! That looks like a violin.” I exclaimed.

“Aye,” he confirmed, “It’s a fiddle, richt eneuch.” His eyes took on a faraway look. “The man resting here is still spoken of with reverence amongst my people. Sk’ottsk’inner, he was called and it is said that he was the greatest fiddlin’ mannie of his time.

This was in the age before the’ Hard Times’, you unnerstan’, afore the mad god K’ooncil and his minions demanded the sacrifice of all things musical and the skills and arts became lost tae us.” He shook his head, sadly.

“Did nothing survive?” I asked.

“Legend speaks of some who rebelled, who turned their backs on the harsh gods of that time and, with the instruments of their craft, disappeared from common view.” He paused thoughtfully. “It may be that they found refuge in the ‘baneyairds’ and that their descendants still bide here in these harsh lands. It would explain this offering.” I was touched by the man’s rough dignity.

“Well, let’s get on.” I said. D’oad conferred with the bearers then turned to me.

“We must have a F’lykup.” he announced. My heart sank.Our expedition had all too often been hampered – not to say plagued – by this ritual. Whenever the natives divined that the ‘natural harmonies’ were disturbed, they would perform this propitiatory ceremony and, in extreme cases, the F’uncipeece’ would also be invoked.

My medical kit included water-purifying tablets and my anti-doric medication

The bearers began producing small, garishly-coloured pastries to be ritually exchanged and consumed. Resigned to a long delay, I turned to D’oad. “I shall take no part in this.” I told him,” I respect your beliefs but I do not fear ‘evil spirits’.” He looked at me admiringly and shook his head.

“Yerrachube, M’in.” he said.

“A lucky accident of birth and education.” I replied modestly as he rejoined his men.

Finding a mossy stump to rest against, I began a careful inventory of the personal belongings in my own backpack. My medical kit included water-purifying tablets and my anti-doric medication. This was an experimental drug produced by my family’s pharmaceutical company. We had been commissioned by the Trumpistani government to investigate the nature of this affliction which was endemic to the entire region. Recent outbreaks in Trumpistan had cost the empire dear in lost revenue from its massive tourist industry.

How the infection was transmitted remained unclear but it appeared to affect the speech centres of the brain resulting in a form of mostly benign (physiologically, at least) dyslexia which rendered the victims unintelligible save to fellow sufferers. I had agreed to’ field test’ the results of our latest research which, it was hoped, would provide protection not only against ‘Doric’ but also ‘Lallans’, ‘Orcadian’, ‘Shetlandic’, so-called ‘Romany Cant’ and Scots (though not Irish) Gaelic. I had been dosing myself regularly since arriving in the country and estimated that there remained enough for several more weeks.

Reclining comfortably, I gazed around at the lush tangle of exotic greenery, and inhaled the unfamiliar perfumes of strange blossoms. My eyelids grew heavy but, just before I fell into a doze, I heard (or thought I heard) wild, joyful music played upon all manner of instruments and I glimpsed (or fancied I glimpsed) figures dancing gracefully beyond the leafy walls surrounding me.

To be continued…….